I first wrote about this heartbreaking topic in 2013. Sadly, our country’s treatment of Native Americans hasn’t changed much.

Does that title offend the living crap out of you? It did me, believe it. I didn’t make it up; it is attributed to a United States Army officer in the late nineteenth century. More on that shortly. The line would become the buzz phrase for many non-reservation Native American boarding schools—these representing one of the darkest chapters in this country’s history with regard to its abominable treatment of the indigenous people—those who were here first.

Fr. Junípero Serra

Long before the advent of the boarding schools, Euro-Americans were set on forcing their ways on the people that they called “Indians.” As far back as the early seventeenth century—not long after Europeans first settled here—a priest in the Society of Jesus told the chief of a tribe in what is now Maryland that he wanted “…to extend civilization and instruction to his ignorant race, and show them the way to heaven.” This sort of hubris extended all through the colonial period.

The eighteenth century brought the Spanish missionaries, led by Father Junipero Serra. (See my post, “California Genocide.”) As he established his string of missions and attempted to “educate” the poor savages, he couldn’t help but think, “When I saw their general behavior, their pleasing ways and engaging manners, my heart was broken to think that they were still deprived of the light of the Holy Gospel.” He then tried to convert all the Indians he encountered to Christianity.

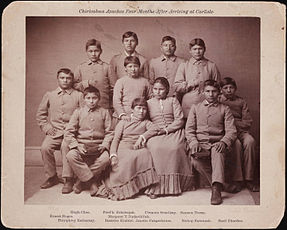

Carlisle students around the turn of the century,

In the nineteenth century, westward expansion brought white America to the Great Plains and beyond, which brought about decades of what became known as the Indian Wars. Subsequent subjugation of all Native American tribes led to their confinement on reservations, which brought more Christian missionaries bound and determined to turn them from their heathen ways. They set up their schools where the Indians now lived.

The first non-reservation Native American boarding school, the Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Pennsylvania, was founded in 1879 by Richard Henry Pratt, a military officer who had fought in the Indian Wars. Pratt’s philosophy was evident in a speech that he gave: “A great general has said that the only good Indian is a dead one, and that high sanction of his destruction has been an enormous factor in promoting Indian massacres. In a sense, I agree with the sentiment, but only in this: that all the Indian there is in the race should be dead. Kill the Indian in him, and save the man.”

In other words, let us abuse and defile an entire culture.

A group of fierce, proud Apaches a few months after immersion at a boarding school.

Carlisle served as a model for numerous off-reservation boarding schools, many of which were operated by religious organizations and supported by government funding. Children were taken from their homes—oftentimes by force, against the wishes of their parents—and sent to the schools, which did their best to kill the Indian inside them. Their hair was shorn (a source of humiliation for boys from many tribes); they wore uniforms; they were given Americanized names; they could not speak their own language; they were “encouraged” to become Christians.

Discipline in these boarding schools was harsh. Physical, emotional, even sexual abuse was not uncommon. There were many reports of children being starved, beaten, and confined. A 1928 survey determined that infectious diseases were widespread at the boarding schools from poor nutrition due to lack of funding, as well as overcrowding, poor sanitation, and hard labor. The survey also noted that the death rate for Native American children in boarding schools was more than six times that of any other ethnic group. And for many who made it to adulthood, alcoholism and suicide were not uncommon.

A 1960s government report stated that the majority of teachers in boarding schools believed that their role was to “civilize” Native American children, not educate them. Discipline and punishment were still the keys.

Fortunately, this and other surveys led to the passage of the Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act of 1975. This took the emphasis away from boarding schools and put it on community schools. The large majority of non-reservation Indian boarding schools shut down in the 1980s and ’90s. Few remain today, and those that do, such as the Sherman Indian High School in Southern California, embrace their heritage and culture while preparing students for their future in this multi-cultural world. Let us hope that “Kill the Indian” remains a part of the dark past.

OLDER THAN AMERICA

A haunting film titled, Older than America addresses the dark side of Native American boarding schools and their role in cultural genocide. Georgina Lightning wrote and directed this 2008 movie, and she also stars in it as Rain Many Lightnings O’Rourke. The excellent cast includes Academy Award nominee Bradley Cooper and the outstanding First Nations (Canada) actor, Adam Beach (Windtalkers, Smoke Signals), among others.

A haunting film titled, Older than America addresses the dark side of Native American boarding schools and their role in cultural genocide. Georgina Lightning wrote and directed this 2008 movie, and she also stars in it as Rain Many Lightnings O’Rourke. The excellent cast includes Academy Award nominee Bradley Cooper and the outstanding First Nations (Canada) actor, Adam Beach (Windtalkers, Smoke Signals), among others.

Rain, a schoolteacher on the Fond du Lac reservation in Minnesota, is troubled by visions from a nearby eerie Indian boarding school, now shut down. Terrible atrocities happened there decades ago when Rain’s mother, now institutionalized and practically comatose, attended the school. As Rain, with the help of her cop fiancé (Beach) and a seismologist (Cooper), draws closer to the truth, she also learns that there are others who will stop at nothing to ensure that the past remains buried.

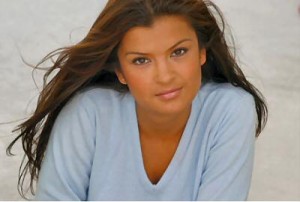

Georgina Lightning

For Georgina Lightning, this was a story that needed to be told. Her father had attended an Indian boarding school, and while he never talked about it when she was a child, his violent outbursts often troubled her. He committed suicide when Lightning was eighteen. Subsequently she set out to learn more about his past, which led her to the boarding school that he attended. There, she found a large cemetery on the grounds, with countless headstones of children that had died there. The idea for her story emerged from that, and as you’ll see, the cemetery is a key plot point in Older than America.

Jacqueline and I have seen numerous contemporary Native American films. Older than America ranks as one of the best.

I clicked on the Like button not for the topic but for the fact that you shared this sad information. ;0) Of course this has been a topic that has bothered me all my life. Many of the misguided conceptions in our history are nicely summed up in the quote you shared, “As he established his string of missions and attempted to “educate” the poor savages, he couldn’t help but think, “When I saw their general behavior, their pleasing ways and engaging manners, my heart was broken to think that they were still deprived of the light of the Holy Gospel.” Yeah, like their pleasing ways and engaging manners weren’t a sign they were doing something right! Grrrr

Yeah, Indy, I wish they had a “Sad” button. It is this kind of hubris that STILL makes our country far less than it could be. It is shameful.