French novelist Jules Verne is often referred to as the “Father of Science Fiction.” You’ll get no argument from me. This post, about one of his most famous works, first ran in 2015.

My muse, Edgar Rice Burroughs, wrote his adventure novel, At the Earth’s Core, in 1914. Six more books followed in what is known as his Pellucidar series. But more than likely ERB was influenced by a novel written over fifty years earlier by a French author named Jules Verne. Journey to the Center of the Earth was a remarkable literary achievement for the nineteenth century—or for that matter, any other time.

My muse, Edgar Rice Burroughs, wrote his adventure novel, At the Earth’s Core, in 1914. Six more books followed in what is known as his Pellucidar series. But more than likely ERB was influenced by a novel written over fifty years earlier by a French author named Jules Verne. Journey to the Center of the Earth was a remarkable literary achievement for the nineteenth century—or for that matter, any other time.

TO ICELAND AND BELOW

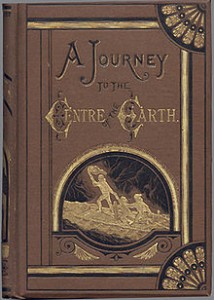

Initially published in 1863, the first English edition of Journey to the Center of the Earth appeared in 1871. Its title translated alternately to A Journey to the Centre of the Earth and A Journey to the Interior of the Earth. The prolific Verne wrote it as the third book in his series, Les Voyages Extraordinaires (The Extraordinary Voyages Series). Other famous works would follow as part of the series, among them Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea, Around the World in Eighty Days, and Mysterious Island.

An 1878 edition.

The story’s narrator, a young man named Axel, lives with and works for his uncle, Professor Otto Liedenbrock, in Hamburg, Germany. A renowned college lecturer and an authority in the field of mineralogy, Liedenbrock has made an interesting discovery. Inside an old book he has found a cryptic note written by a long-dead Icelandic explorer named Arne Saknussemm. He and Axel manage to break the code and are stunned to read that Saknussemm claims to have discovered a passage into the center of the Earth. The entrance is in one of the craters of Iceland’s Snæfell volcano. Liedenbrock sets out for Iceland with his reluctant nephew in tow. The whiny Axel is not a guy you would want to take along on an adventure.

MUSHROOMS AND MONSTERS

In Reykjavik they hire a big, quiet guide named Hans, who serves them well all through the story but hardly says a word. With Axel bitching along the way they travel overland to the Snæfell volcano, where the correct crater is shown to them by the shadow of a nearby mountain, according to Saknussemm’s note.

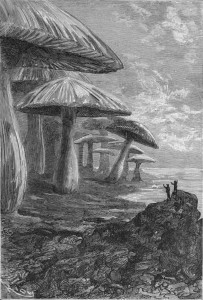

One of the original illustrations in the book.

So down they go, traveling many hundreds of miles and encountering all manner of strange geological phenomena. At one point they run out of water, and Axel (probably thinking, “See, I told you so!”) nearly dies. But Hans taps into an underground river running through a parallel chamber, and they are able to follow the new stream in their tunnel farther downward. Axel, of course, becomes separated from the others and is lost for days, but they are eventually reunited.

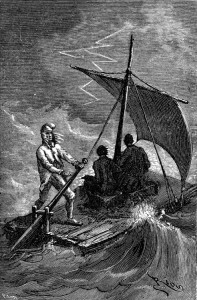

Well along the journey they emerge into an unbelievably vast cavern, which exists in perpetual daylight from electrically charged gas. They stand on the shore of a subterranean ocean, where they gaze at a nearby forest of petrified trees, and mushrooms the height of the Washington Monument. Liedenbrock insists that they must cross the sea to another shore, where they can continue the journey. They build a raft and set out across the ocean, where they witness frightening battles between prehistoric creatures, these giant monsters nearly destroying them.

Ultimately, a storm casts them onto another shore. There, they discover all sorts of prehistoric flora and fauna, including a herd of mastodons. Axel, who is finally getting with the program, finds what appears to be a large human skull. And, most shockingly, they spot what looks like a twelve-foot human or humanoid—either a man-like ape or an ape-like man. Not really wanting to find out, fearing there may be many more, they beat a hasty retreat.

Our intrepid explorers soon discover a passage marked by Arne Saknussemm himself as leading to the true center of the Earth. What ensues is a portion of the journey that out-thrills any thrill ride at any theme park on the planet. Accordingly, I will stop here rather than call a spoiler alert. If you’ve never read Journey to the Center of the Earth, or—like me—if you haven’t read it since you were a kid, you might want to give it a try.

Our intrepid explorers soon discover a passage marked by Arne Saknussemm himself as leading to the true center of the Earth. What ensues is a portion of the journey that out-thrills any thrill ride at any theme park on the planet. Accordingly, I will stop here rather than call a spoiler alert. If you’ve never read Journey to the Center of the Earth, or—like me—if you haven’t read it since you were a kid, you might want to give it a try.

THE STORY ENDURES IN OTHER MEDIA

Theatrical and TV movies, direct-to-DVD films, board games, animated TV series, comics, theme park rides, radio broadcasts and more have all been based on Journey to the Center of the Earth. They even made a stage play out of the story, for crying out loud! I can’t get my head around how that would work.

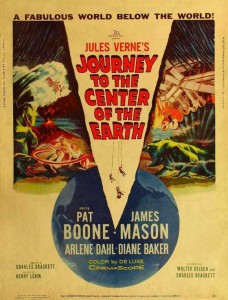

The 1959 film version of the story is perhaps the most endearing and enduring of them all. Liedenbrock becomes Professor Lindenbrook (James Mason) of Scotland; Axel is now Alec (Pat Boone), his enthusiastic student; Hans is still Hans, but this time he brings Gertrud, his pet duck, on the journey. There are villains, and even a woman (Arlene Dahl). Sure, the special effects are dated—no CGI then—but this is still a fun movie.

The 1959 film version of the story is perhaps the most endearing and enduring of them all. Liedenbrock becomes Professor Lindenbrook (James Mason) of Scotland; Axel is now Alec (Pat Boone), his enthusiastic student; Hans is still Hans, but this time he brings Gertrud, his pet duck, on the journey. There are villains, and even a woman (Arlene Dahl). Sure, the special effects are dated—no CGI then—but this is still a fun movie.

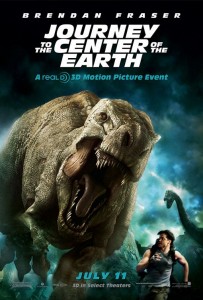

Perhaps the most interesting version is the 3-D film, Journey to the Center of the Earth, starring Brendan Fraser (big fan). The story posits that Verne’s novel was not fiction but fact, as were most of his books, and that a dedicated group of Vernians have attempted to travel in the footsteps of Professor Liedenbrock and other characters.

Volcanologist Trevor Anderson (Fraser) learns that his late brother, Max, was a Vernian. Max died ten years earlier (inside the Earth’s core, which we see at the start of the film but which Trevor doesn’t know). Using Max’s heavily marked-up copy of Journey to the Center of the Earth as a guidebook, Trevor travels to Iceland with Max’s son to retrace the route that Max—and Liedenbrock—took through the Snæfell volcano. This is an exciting romp through the original story, this time with all of the CGI effects that you could want, including 3-D.

Volcanologist Trevor Anderson (Fraser) learns that his late brother, Max, was a Vernian. Max died ten years earlier (inside the Earth’s core, which we see at the start of the film but which Trevor doesn’t know). Using Max’s heavily marked-up copy of Journey to the Center of the Earth as a guidebook, Trevor travels to Iceland with Max’s son to retrace the route that Max—and Liedenbrock—took through the Snæfell volcano. This is an exciting romp through the original story, this time with all of the CGI effects that you could want, including 3-D.

And who is to say that Arne Saknussemm, Professor Otto Liedenbrock and others were not just figments of Jules Verne’s imagination?