If the 1979 novel, The Neverending Story, by German author Michael Ende, is a book about a book, then I suppose the 1984 film adaptation, The NeverEnding Story, can be referred to as a movie about a book about a book. But why make ourselves crazy thinking about that? The main thing is that this fairytale/fantasy, while well loved by children, has a most important message for adults. More on that shortly.

If the 1979 novel, The Neverending Story, by German author Michael Ende, is a book about a book, then I suppose the 1984 film adaptation, The NeverEnding Story, can be referred to as a movie about a book about a book. But why make ourselves crazy thinking about that? The main thing is that this fairytale/fantasy, while well loved by children, has a most important message for adults. More on that shortly.

“GET YOUR HEAD OUT OF THE CLOUDS”

Bastian is a lonely young boy being raised by his widower dad, a boring “suit” kind of guy. At breakfast he lectures his book-loving son about the perils of living in a fantasy world. He advises Bastian to get his head out of the clouds, to keep his feet firmly planted on the ground, and other yawner clichés like that.

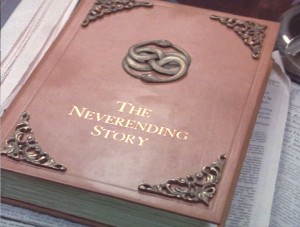

On his way to school, Bastian is chased by three bullies. He hides out in a bookstore, where he encounters curmudgeonly Mr. Coreander, who doesn’t like kids—he thinks they’re all more interested in video games than reading books. Bastian convinces him otherwise and then asks Coreander what he’s reading—a large book with a strange medallion on the cover. It’s called The NeverEnding Story, but—as the old man warns Bastian—“It’s not for you.” This only makes the boy more curious.

On his way to school, Bastian is chased by three bullies. He hides out in a bookstore, where he encounters curmudgeonly Mr. Coreander, who doesn’t like kids—he thinks they’re all more interested in video games than reading books. Bastian convinces him otherwise and then asks Coreander what he’s reading—a large book with a strange medallion on the cover. It’s called The NeverEnding Story, but—as the old man warns Bastian—“It’s not for you.” This only makes the boy more curious.

When Coreander is called away for a minute, Bastian steals the book and runs off. The old man finds a note from the boy, promising to return it. He doesn’t seem upset by the theft; on the contrary, he smiles, as if it was what he had expected.

THE EMPRESS IS DYING

Skipping class, Bastian climbs up to the school attic and begins reading. The story is about an imaginary world called Fantasia (Fantastica, in the novel), a once-joyous place now being threatened by a dark storm called The Nothing, which threatens to overrun the land. Many of its inhabitants—Rockbiters, teeny people, Nighthobs and others—travel to the Ivory Tower to beseech the Childlike Empress, ruler of Fantasia, for help. They are told she is gravely ill, and that a warrior of the Plains has been summoned to go on a quest and find a cure for her. Only then can Fantasia be saved.

Bastian finds the book pretty intense.

The warrior turns out to be a boy named Atreyu (a Native American; loved that), much to everyone’s surprise. He is given a medallion called AURYN, which is supposed to protect him on his journey. It is the same symbol on the cover of Bastian’s book. At the moment that Atreyu sets out, The Nothing dispatches a werewolf called Gmork to hunt the boy down and kill him.

SADNESS AND LUCK

Atreyu rides his horse, Artax, for what seems forever in search of the ancient Morla, purported to be the wisest being in Fantasia. He finds Morla in the Swamps of Sadness, but at great cost as Artax, overwhelmed by the sadness, sinks into the bog. Morla turns out to be a giant, weird-looking turtle, whose description causes both Atreyu and Bastian to scream. Atreyu and Morla hear Bastian’s cry, the first indication that Bastian is more linked with the story than just reading it.

Falkor likes Atreyu to scratch behind his ear.

Morla cannot help, but he tells Atreyu to seek out the Southern Oracle—it’s only ten thousand miles away. Disheartened and injured, Atreyu schleps through the mud and is about ready to pack it in as the Gmork nears. That’s when the boy is plucked up into the air and saved by a luck dragon named Falkor—a sort of giant worm with a kindly dog face.

When Atreyu awakens days later, he finds that Falkor has borne him nearly the entire ten thousand miles to the Southern Oracle. His wounds have been tended to by a couple of outrageous gnomes—the story’s comic relief. They warn him that approaching the Southern Oracle will not be easy. Still, off Atreyu goes to face two challenges.

ONLY A HUMAN CHILD WILL DO

After surviving the first challenge—a couple of huge statues that shoot bolts of lightning from their eyes—Atreyu finds the second one most unnerving. His “true self” is revealed in a mirror, and that self turns out to be—none other than Bastian, who now, freaked out, throws the book aside. Eventually he resumes reading and finds Atreyu, now past the mirror, standing before the Southern Oracle, another couple of huge statues. He is told that the Childlike Empress can only be saved if she is given a new name. Easy, Atreyu thinks. Wrong-o. The name must be given by a human child from outside the boundaries of Fantasia.

The Gmork

What the hey, thinks Atreyu. He has no clue where the boundaries of his world are. Atop Falkor, he frantically rides all over the place as The Nothing closes in, and as the storm rages he is knocked off the luck dragon into the Sea of Possibilities, where he loses AURYN. He is washed ashore and comes across a ruined town, where he encounters a subdued Gmork. The werewolf explains that Fantasia represents the imagination of children, their dreams, their fantasies, their creativity. The Nothing, on the other hand, is the apathy of adults, their cynicism, their attitude of “get your head out of the clouds” and “keep both feet on the ground.” If they forget their hopes and dreams, an emptiness—The Nothing—overtakes them. They then do battle as the storm rages, and Atreyu kills the Gmork. He is saved by Falkor, who has found AURYN, and they fly off as the town—and most all of Fantasia—vanishes.

BASTIAN, CALL MY NAME!

Atreyu and Falkor are now flying around in space, with chunks of large rocks—all that remains of Fantasia—floating past them. One rock holds the Ivory Tower, where Atreyu finally meets the Childlike Empress. He failed her, Atreyu says. No, you didn’t, the Empress tells him. She explains that Atreyu has brought the human child with him, that he’s been with Atreyu through all of his adventures. Bastian, reading furiously, still finds this impossible to believe, until the Empress addresses him directly and pleads with him to call her new name as what is left of Fantasia continues to crumble. Bastian at first resists, saying that he has to keep his feet on the ground. Finally he calls out the name, “Moon Child”—his mother’s name.

AURYN represents infinity/eternity.

Bastian now appears with the Empress, who holds a grain of sand—all that remains of Fantasia. She tells him that Fantasia can rise anew from his dreams and wishes. She gives him AURYN, on the back of which is written, “Do What You Wish.” And so Bastian makes his wishes. He first rides atop Falkor across a new and even more splendid Fantasia, waving at all of its inhabitants—including Atreyu and Artax. Next, he and Falkor swoop down to scare the crap out of the bullies that chased him. As they ride off, a narrator tells us that Bastian had many more adventures in Fantasia, adding, “But that’s another story.”

WHAT, AN UNHAPPY AUTHOR?

A side note on The NeverEnding Story. The movie covers only the first half of the book, and the author, Michael Ende, did not feel it conveyed the full meaning of his title. He asked for production to be stopped until they worked it out, or at least for the title to be changed. When neither happened, he sued the producers. Need I tell you that he lost?

A sequel, The NeverEnding Story II: The Next Chapter, came out in 1990. It utilized some elements from the rest of the book, but otherwise was a different story. Don’t waste your time; it wasn’t very good. This may be the first film I’ve come across with a 0% rating on Rotten Tomatoes. A second sequel four years later was a comparable bomb.

But the original is a fine movie that offers an outstanding message. It’s not a “kid’s movie” per se, but a good family movie. All I know is my three daughters couldn’t get enough of it after it came out on VHS tape back in the eighties. I don’t doubt that they, along with their kids, are watching it to this day.

One final note: as a writer and creator of quite a few fantasy worlds, I leaned way too far to the right (brain) for too long and was forced to “get my head out of the clouds” in order to survive. (Read: pay the bills, have a life, etc.) But I never lost my imagination, my ability to dream, and accordingly I can sum up the point of this in one word: BALANCE.

Wonderful post Mike. As a kid I loved this film and read the book after.

Thanks, David. An entertaining film that has a strong message can’t be beat, eh?

True. I watched it a year or so ago and as an adult it kind of falls a little flat, but for kids, it is so full of wonder.