I first presented this post in 2012. Be forewarned: the scene I chose to share is heartbreaking.

Those of us who write novels have a great platform for saying pretty much anything we want. The characters we create often reflect our likes, our dislikes, our politics, our worldviews, and many other things. And there is nothing wrong with venting our spleens through fiction—with one caveat.

Those of us who write novels have a great platform for saying pretty much anything we want. The characters we create often reflect our likes, our dislikes, our politics, our worldviews, and many other things. And there is nothing wrong with venting our spleens through fiction—with one caveat.

As a writing coach and editor back since the dawn of time I’ve read countless manuscripts by both aspiring and successful novelists, and almost without exception each has something of a more personal nature to say. When the occasional bit of soapboxing occurs within the context of a good, fast-paced story, no problem. But when the writer’s venting turns into ranting and becomes the story, he or she will quickly lose the readers. I assure you, I’ve seen plenty of that, and I’m hardly shy about pointing that out to the writer. You want to spend chapter after chapter on a pet peeve of yours? Write a non-fiction book.

So how do you not overwhelm readers with your venting? Okay, I had a lot to vent about in my Native American-themed ghost story, The Burning Ground. The story revolves around a small band of Maidu Indians in the Sierra Nevada mountains, all of whom are killed by miners during the Gold Rush. In the main contemporary story their graves are desecrated by artifact hunters, and the pissed-off spirits exact some nasty revenge. (See my post: “Angry Spirits from the Gold Rush Era Return with a Vengeance.”)

I knew that there had been problems between whites and Indians during the Gold Rush, but not until I did extensive research for the sake of accuracy did I realize the magnitude of the slaughter, in which entire tribes were all but annihilated. This led me into research on much of California’s indigenous population, whose extermination had actually begun as far back as the arrival of the Spanish missionaries. (See my post, “California Genocide.”) These atrocities, along with the ongoing issues of grave desecration, gave me plenty of cause to vent.

I knew that there had been problems between whites and Indians during the Gold Rush, but not until I did extensive research for the sake of accuracy did I realize the magnitude of the slaughter, in which entire tribes were all but annihilated. This led me into research on much of California’s indigenous population, whose extermination had actually begun as far back as the arrival of the Spanish missionaries. (See my post, “California Genocide.”) These atrocities, along with the ongoing issues of grave desecration, gave me plenty of cause to vent.

But how not to climb up on the big soapbox and stay there? In the extensive opening chapter I introduce a number of characters, both Maidu and white man, and show how a small misunderstanding leads to a minor incident, which leads to a major incident, which leads to a killing, which leads to a slaughter, which leads to vengeance. Operative word: SHOW. Readers experience a representative scene, but the point is made. I vented with impunity.

In the contemporary story a young boy learns that his father is a grave robber, a “thief of time,” and from his youthful perspective he muses over how wrong this practice is. I’m still venting, but I’m not on the soapbox.

Finally, much farther into the book—when I’ve hopefully long hooked my readers—a Maidu descendent dramatically relates the sad history of his people to the main characters. I’ve put him on the soapbox for a few pages, and I’ve gotten to vent—but also entertain, and not be in the reader’s face.

I used my 1993 satirical science fiction novel, Bicycling Through Space and Time, for one of my more intense rounds of venting. Members of my parents’ families perished during the Holocaust in Europe, and I grew up in New York City not understanding why many of our dour neighbors had numbers burned into their arms. When I finally did…

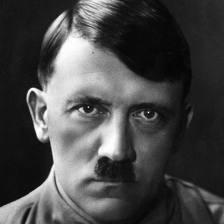

To set the upcoming scene: this book, first of a trilogy, is mostly outrageous humor as bicyclist/writer Jack Miller travels around on a mountain bike that has an extra gear implanted by an alien Study Group, led by a being whom Jack calls the Old Guy. In chapter seven Jack winds up in 1896 Austria. (According to the Study Group’s “Prime Directive” he cannot interfere with anything that happened in the past, of course.) He rides by a farm, where three little boys are playing cowboys and Indians in a field. Two of the boys leave the field, and Jack talks to them. They’re tired of playing with Dolfie, who is too rough. They also mention the owner of the field, “Herr Hitler.” Jack quickly puts two and two together. Here is the scene:

To set the upcoming scene: this book, first of a trilogy, is mostly outrageous humor as bicyclist/writer Jack Miller travels around on a mountain bike that has an extra gear implanted by an alien Study Group, led by a being whom Jack calls the Old Guy. In chapter seven Jack winds up in 1896 Austria. (According to the Study Group’s “Prime Directive” he cannot interfere with anything that happened in the past, of course.) He rides by a farm, where three little boys are playing cowboys and Indians in a field. Two of the boys leave the field, and Jack talks to them. They’re tired of playing with Dolfie, who is too rough. They also mention the owner of the field, “Herr Hitler.” Jack quickly puts two and two together. Here is the scene:

The kid playing cowboys and Indians was Adolf Hitler.

Hey, Study Group, really testing me, huh?

Just a kid, like kids all over the world; running, playing, not concerned about many things, having a good time…

A kid who would be responsible for the deaths of millions of human beings.

Look at this neat farm. Nine acres, incredible countryside. The kid’s having a ball. But the family would move from here soon, wouldn’t it? Move and move and move. Different towns, different schools, less freedom for a boy whose early ambitions were to be an artist and work in the church.

Why’d you keep moving, Alois and Klara? Didn’t you know? Couldn’t you tell that your son would grow up to be the most awful person who ever lived? Alois, couldn’t you have given as much time to the kid as you did to your bees or your buddies at the tavern?

Dolfie was a hundred feet away, firing in all directions at the pony soldiers who were attacking his village. Sometimes I got in the line of fire.

Dolfie was a hundred feet away, firing in all directions at the pony soldiers who were attacking his village. Sometimes I got in the line of fire.

American Indians. Let me tell you what happened to the American Indians, you little bastard…

What’s going on inside your head? Some Wagnerian opus resounding through it? Does Siegfried and Wotan and Alberich mean anything to you yet?

Farm. Animals. Goose-step…

The kid was closer to the road. He fell to his stomach in the soft grass, rolled over once, dodging imaginary bullets. His gun empty, he unslung an air bow and fired arrows at an alarming rate.

Not fast enough though, is it? Line them up and shoot them by the hundreds. Hang them by the thousands. Gas them by the millions and burn the bodies so they don’t pile up. Make sure you get all the gold fillings first.

Fifty feet away, back on his feet, having as much fun alone as with Otto and Edmund. Not even curious about the mountain bike.

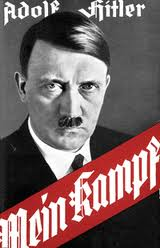

I’m a writer too, kid. Never did anything like Mein Kampf. I have to say, at least you tried to warn them. You tried to give them a look inside your sick mind, tried to tell them what you’d do to the world if you were king.

I’m a writer too, kid. Never did anything like Mein Kampf. I have to say, at least you tried to warn them. You tried to give them a look inside your sick mind, tried to tell them what you’d do to the world if you were king.

If.

Twelve years of your Third Reich, twelve years of crushing all the little guys and standing up to the big guys. Scared the hell out of them, too. Gave the world a few bad dreams. But it could’ve been worse, could’ve been a Thousand Years, like you’d predicted.

Dolfie was twenty-five feet away. I clenched the handlebars tightly; would’ve liked it to be his throat. That’s it, I could kill him. Hop the fence, strangle the shit out of him, whap his head against a tree for good measure. But you’d bring him back to life, wouldn’t you, Old Guy? Because that’s the way it has to be.

Because that’s the way it was.

Wouldn’t he stay dead in some time plane? This was crazy. If I did it, I’d never be able to travel the Ultimate Bike Path again. It would be worth it, though. Personal gratification. But for how long? Enjoy it for a moment, then wind up like hamburger meat in a Cuisinart. That’s what would happen, right?

Why did you have to bring me here? It’s not fair.

Dolfie was fifteen feet away, still fending off bad guys. I pointed a finger at him. “Hey, kid.”

He looked up. “Yes, sir?” As polite as Otto and Edmund.

“Bang, you’re dead.”

He took the cue. Good little actor. Falling to the grass, he clutched at his chest and made all kinds of moaning sounds as he rolled around.

I biked away from the farm in Hafeld, leaving Adolf Hitler in his death throes.

Cathartic? Yeah, I suppose so. I wrote this scene over the course of two days, and the actual writing went something like this: write and cry, cry and write, write and cry, cry and write. It is, arguably, one of the hardest things I’ve ever written.

But, I got to vent.

Beautiful stated, Mike. And I agree, the venting has to fit the character, time and place or it becomes the author ranting and takes the reader out of the story. Another interesting aspect is when I’ve had to convince the reader of a point of view that was opposite of my own personal beliefs, yet true to the character. Even more fun was a scene in which two characters had opposing views on the same topic – and I had to show the reasoning behind both of them and make them both believable. We writers get to grow a lot in those incidences.

Thanks, Indy. Yes, writing a scene that is the opposite of our personal beliefs is just as difficult, if not more so. Case in point: the hate speech that I wrote for a neo-Nazi in FREEDOM’S HAND. That one really got to me.