The Civil War didn’t kill these soldiers, but what came afterward did. I first presented this post in 2021.

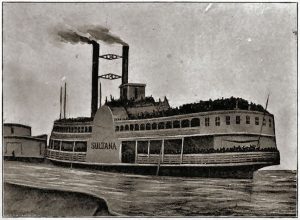

The SS Sultana, prior to departing Vicksburg.

Imagine that you’re a Union soldier imprisoned by the Confederacy during the Civil War. When the war ends you and your fellow prisoners are freed, and you’re finally going home! But you never make it there. Why? Because your northward journey up the Mississippi River is aboard the ill-fated SS Sultana.

GREED PREVAILS, AS ALWAYS

The commercial paddle-wheel steamboat, SS Sultana, was first launched in 1863, its primary purpose to transport cotton between St. Louis and New Orleans. In April of 1865, shortly after the assassination of President Lincoln, the vessel, under the command of Captain James Mason, headed south, bound for New Orleans.

Stopping in Vicksburg, Mississippi, Mason was approached by the city’s quartermaster, Reuben Hatch, with an interesting proposition. Thousands of recently released Union prisoners now occupied a parole camp outside Vicksburg. Hatch told Mason that the government would pay $2.75 per enlisted man, and $8 per officer, to any paddle-boat captain who would take a group of them north. Hatch could guarantee up to 1,400 men, and of course he would receive a kickback. Mason readily agreed, saying that he would pick up the group on his way back from New Orleans. The fact that the Sultana had been built with a capacity for 376 people did not appear to concern either man.

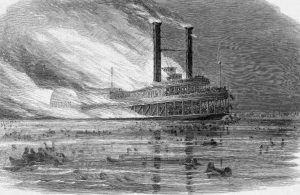

A depiction of the devastating explosion.

NO TIME FOR ADEQUATE REPAIRS

Mason continued on to New Orleans, spreading news along the way of Lincoln’s assassination. On April 21, with 70 paying passengers and a crew of 85, The Sultana once again headed north. Before reaching Vicksburg, one of its four boilers began leaking. Under limited pressure the paddle-wheeler arrived at Vicksburg to pick up the freed prisoners, and to have the boiler repaired.

As the men were being loaded onto the vessel, a mechanic hired by Mason to repair the boiler reported that a seam had ruptured and needed to be replaced. Mason knew that this would take days and likely cost him the profitable human cargo. His chief engineer convinced the mechanic to do a patchwork job so that they could get underway.

The 1,400 soldiers that Mason expected somehow turned into about 1,900. In all, over 2,100 people were crammed onto the Sultana, way beyond capacity when it departed Vicksburg on the night of April 24.

The 1,400 soldiers that Mason expected somehow turned into about 1,900. In all, over 2,100 people were crammed onto the Sultana, way beyond capacity when it departed Vicksburg on the night of April 24.

DISASTER

Battling one of the worst floods in the history of the Mississippi River, the Sultana arrived in Memphis on the night of April 26. Some cargo was unloaded, and about 200 men disembarked. By 1 a.m. the Sultana headed north again.

At 2 a.m. on April 27, 1865, about seven miles north of Memphis, its boilers exploded, one after another. Steam, then flames, ripped through the crowded deck, as well as the pilot house, leaving no one to steer the vessel. Passengers were thrown into the surging river, some alive, many already dead. The two smokestacks toppled down upon the now burning decks, crushing many. Others that survived the steam, the fire, and all else aboard the doomed paddle-boat either drowned or died of hypothermia in the icy waters of the river.

The SS Sultana—what remained of it—drifted for six miles, finally sinking near Marion, Arkansas.

The first vessel to reach the site of the disaster arrived less than an hour after the explosion and managed to rescue a number of survivors. Bodies continued to be found downriver for months thereafter, while others were never found. Captain James Mason and many of his officers were among the dead.

The final death toll from the tragedy of the SS Sultana ranged between 1,100 and 1,500 people, the worst maritime disaster in U.S. history. No one was held accountable.