This inexplicable mystery, now a century-and-a-half old, has yet to be solved. I first presented this post in 2019.

A natural disaster? An assault by pirates? A murderous plot by the crew? An attack by a giant sea creature? Paranormal activity? All of these suggestions, and more, have been tossed about with regard to the mystery of the Mary Celeste, a bizarre incident that remains unresolved to this day, a century and a half later.

A CURSED SHIP?

The Amazon, later called the Mary Celeste.

The Mary Celeste, a merchant brigantine ship, was built in Nova Scotia in 1860-1861. It was launched in May of ’61 under British registry and originally christened Amazon. (Though I doubt if it made any one-day deliveries back then.) On its initial voyage to carry a load of lumber to England its captain, Robert McLellan, became ill. The ship turned around and took McLellan back to Nova Scotia, where he died shortly after. Was this an omen of things to come?

Problems plagued the Amazon over the ensuing few years. There were a number of collisions, including one in the English Channel, which resulted in the sinking of a brig. Then, in 1867, a storm drove the ship ashore on Cape Breton Island, off Nova Scotia. Its extensive damage prompted her owners to abandon it as a wreck.

An investor acquired the Amazon as a derelict shortly after and sold it to a businessman in Nova Scotia, who in turn sold it a year later to an American mariner named Haines. After restoring the vessel Haines registered it under a new name, the Mary Celeste.

A ROUTINE VOYAGE

After passing a few more times from one consortium of investors to another, the ship underwent an extensive refit in 1872 at Pier 50 in New York City. By October it was ready to take on cargo under its new captain, Benjamin Briggs, who was also one of the investors.

Did a giant sea creature attack the ship?

Briggs, thirty-seven, was an experienced seaman from New England. He and his wife, Sarah, had two children, seven-year-old Arthur and two-year-old Sophia. When he took command of the Mary Celeste he arranged for his wife and daughter to accompany him on the refitted ship’s maiden voyage. His son, still in school, would remain at home with his grandmother.

The crew that Briggs selected for the refitted ship’s maiden voyage to Genoa, Italy consisted of seven experienced mariners. They took on a cargo of denatured alcohol at Pier 50 and sailed into New York Harbor, where they lay at anchor until some bad weather passed. On November 7 the Mary Celeste headed out into the Atlantic.

At the same time another merchant brigantine, the Dei Gratia, under captain David Morehouse, lay at anchor in New Jersey awaiting a cargo of petroleum, their ultimate destination Genoa, same as the Mary Celeste. They departed on November 15.

WHERE ARE THEY?

On December 5 the Dei Gratia sailed at a point between the Azores and the Portuguese coast. There, a vessel was spotted a few miles away, headed right for the Dei Gratia along an erratic course. As it neared, Morehouse could not see anyone on deck, and he was stunned to notice its name: the Mary Celeste. He knew Benjamin Briggs quite well, and this unexpected encounter concerned him.

Morehouse immediately sent his first and second mates to check it out. They searched every inch of the ship and then reported back to the anxious captain: there was not a trace of Briggs, his wife and daughter, or the seven crewmen anywhere on board. The Mary Celeste was a ghost ship.

Morehouse immediately sent his first and second mates to check it out. They searched every inch of the ship and then reported back to the anxious captain: there was not a trace of Briggs, his wife and daughter, or the seven crewmen anywhere on board. The Mary Celeste was a ghost ship.

What else did Morehouse’s men find on the brigantine? Its only lifeboat was gone; some sails and rigging were damaged or missing; the main hatch was closed but two others were open; the captain’s navigational instruments were not where they could usually be found; there were no signs of violence. Some water had gotten into the hold, though not enough to raise a red flag. The first bit of speculation by Morehouse and his men: Benjamin Briggs, his family, and the seven crewmen had abandoned the ship in the lifeboat. But why did they do this?

The logbook of the Mary Celeste, found in a seaman’s cabin, offered no answers to the mystery. Its final entry was made ten days earlier and simply noted its location as being four hundred nautical miles from where the Dei Gratia found her.

AFTERMATH

Captain Morehouse, judging the Mary Celeste to be a derelict, decided to sail it into Gibraltar and put in a salvage claim. That would open a new can of worms, many believing that a crime had been committed in the disappearance of the ten people. Conspiracy theories abounded, and most were certain that foul play was involved. But nothing could be proven, because Benjamin Briggs, his family, and seven crewmen, who seemingly abandoned ship in a lifeboat, would never be seen again.

The court released the Mary Celeste in March of 1873. Under a new captain and crew, the brigantine completed its journey to Genoa the following month.

The salvage claim, finally awarded to Morehouse, amounted to about £1,700—barely one-fifth of the estimated value of the Mary Celeste and its cargo. In making the announcement, the chief justice of Gibraltar still came across as believing that the crew of the Dei Gratia were complicit in the incident. Captain David Morehouse and his men would remain guilty in the court of public opinion for a long time to come.

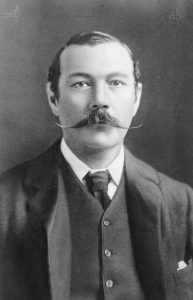

Arthur Conan Doyle

FACTS AND FICTION

The mystery of the Mary Celeste has been speculated upon to this very day—in magazine articles, in books, films, TV documentaries, and more. From a drunken mutiny by the crew to pump congestion to waterspouts to an attack by Riffian pirates from Africa to deadly sea creatures to—yes, even alien abduction, the speculation covers all spectrums of imagination. One historian even posited that Captain Briggs, a devoutly religious man, went apeshit and became the hand of God in killing all of the others, then himself. (This guy later apologized to Briggs’s descendants.)

One fictional story about the Mary Celeste, published in 1884 in Cornhill Magazine, was so influential that many considered it to bear much truth. A twenty-five-year old ship’s surgeon wrote the story. His name: Arthur Conan Doyle. (You’d have to wonder if his most famous creation, Sherlock Holmes, would have solved the mystery.)

The Mary Celeste, which first began its troubled history as Amazon, became a cursed ship, few investors willing to take a chance on her. In 1885 its current captain, Gilman Parker, along with a consortium, conspired to profit from putting an end to the brigantine. They over-insured a worthless cargo for tens of thousands of dollars, then ran the ship aground on an island off the coast of Haiti. The scheme did not work. Parker and his men avoided prosecution, but the dishonored captain died a poor man only months later. Another conspirator went mad, while a third committed suicide.

When author Paul Begg, who wrote about the Mary Celeste (and a whole lot more about Jack the Ripper), summed up his thoughts about the conspiracy case, he also penned a fitting epitaph for the doomed ship. He said, “If the court of man could not punish these men…the curse that has deviled this ship since her first skipper, Robert McLellan, had died on her maiden voyage, could reach beyond the vessel’s watery grave and exact its own terrible retribution.”

When author Paul Begg, who wrote about the Mary Celeste (and a whole lot more about Jack the Ripper), summed up his thoughts about the conspiracy case, he also penned a fitting epitaph for the doomed ship. He said, “If the court of man could not punish these men…the curse that has deviled this ship since her first skipper, Robert McLellan, had died on her maiden voyage, could reach beyond the vessel’s watery grave and exact its own terrible retribution.”