Was renowned writer Thomas Wolfe a stable genius? This post first ran in 2016.

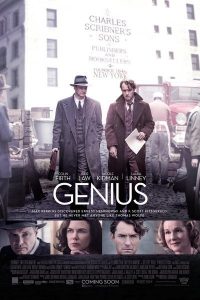

With regard to the 2016 biographical drama, Genius, I could have added “Films About Editors” to my blog as a new series. But really, how many films have book editors, such as the legendary Maxwell Perkins, as the lead character? (Marvel presents, “Red Pencil Man”? Naaah…)

With regard to the 2016 biographical drama, Genius, I could have added “Films About Editors” to my blog as a new series. But really, how many films have book editors, such as the legendary Maxwell Perkins, as the lead character? (Marvel presents, “Red Pencil Man”? Naaah…)

Or, I could have included it as one of my Guilty Pleasures, given that it met both of my parameters. It bombed at the box office, and many of the reviews were negative. But truth be told, I felt no guilt in watching this interesting true story about Maxwell Perkins and his relationship with the “genius” of the title: the novelist Thomas Wolfe.

QUITE A STABLE OF AUTHORS

Maxwell Perkins, formerly a journalist, joined the old New York publishing house of Charles Scribner’s Sons in 1910 as a book editor and worked there until his death in 1947 at the age of sixty-two. Among the authors that he discovered and nurtured were F. Scott Fitzgerald, Ernest Hemingway, Erskine Caldwell, Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings (her novel, The Yearling, won a Pulitzer Prize), James Jones (From Here to Eternity), and—of course—Thomas Wolfe, with whom Perkins fostered a unique relationship. It is in 1929, with their initial meeting, that Genius begins.

Maxwell Perkins was handy with a red pencil.

A calm, quiet man, Maxwell Perkins (Colin Firth) sits at his desk staring at an enormous, handwritten manuscript (over 300,000 words) called O Lost, written by an unknown Southern writer named Thomas Wolfe (Jude Law). It had been recommended to Perkins by Aline Bernstein (Nicole Kidman), a woman who worked for New York City’s Theatre Guild—and with whom Wolfe was having an affair. Wolfe shows up at Perkins’s office, and in a frenetic rant he says that he is sure his autobiographical novel will be rejected by Perkins, as it has been by a number of other publishers. Wrong; Perkins has seen amazing talent in the writing and offers Wolfe a contract—with a warning that a great deal of editing will be necessary before O Lost can be published.

EARLY SUCCESS—AND TURMOIL

Subsequently working together, Perkins and Wolfe often wind up at the editor’s Connecticut home. Wolfe does not endear himself to Perkins’s wife, Louise (Laura Linney), with his motor-mouth rudeness, but their five daughters easily take to him. Wolfe, who lost his dad at a young age, sees Perkins as a father figure, while Wolfe becomes the son that Perkins never had.

Thomas Wolfe presents one of his prodigious manuscripts to Maxwell Perkins.

Months later, over the course of their oftentimes combative work, Perkins has guided Wolfe into cutting more than 90,000 words from O Lost and helped him polish the rest. There only remains the title, which Perkins does not like. He comes up with a new one, and soon after, Look Homeward, Angel is published to great critical and commercial success.

Wolfe, whose ego has him believe that every word he writes is a gem, begins to resent the idea that his sudden success was due mainly to his editor. He writes his next book over the course of two years, his flow of words unstoppable, despite Perkins urging him to wrap it up and deliver the manuscript. When he finally does, it takes a few delivery men schlepping numerous boxes of pages to dump it on the floor of Perkins’s office. Once again a seemingly endless round of editing begins, Wolfe’s obsession with his writing effectively ending his relationship with Aline Bernstein. The result is his second autobiographical novel, Of Time and the River, which is published in 1935.

Aline Bernstein won’t be smiling at Max for long.

A SHORT AND TRAGIC LIFE

Although Of Time and the River becomes an even greater success than Wolfe’s first novel, the constant clashes finally take their toll. He leaves Perkins and Scribner’s for Harper & Brothers, and in 1938 he delivers a manuscript of approximately one million words to his new editor. He then leaves on a trip out west; he’d never been to that part of the country before. Along the way he becomes ill and is soon diagnosed with miliary tuberculosis of the brain. Wolfe is brought to Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore, but the top neurosurgeon in the country cannot help him; the disease has spread too far. He lapses into a coma but comes out of it briefly and asks the nurse for a pad and pencil. Despite his clashes with Maxwell Perkins, Wolfe always considered the editor his closest friend. Now, he writes Perkins a letter that expresses his feelings. He then falls back into a coma and soon dies at the age of thirty-seven.

Perkins, who has attended Wolfe’s funeral, receives the letter soon after. In the film’s final scene, he sits at his desk and reads it. The only thing I’ll say is, make sure you have some tissues handy.

As for those million words that he delivered to Harper, they ultimately became two lengthy, posthumously published novels, The Web and the Rock and You Can’t Go Home Again. His four autobiographical novels became the impressive legacy for Thomas Wolfe.