In last week’s post we left Jack Miller sitting in the waiting area outside the Rock-and-Roll Afterward, wondering who could have summoned him there. I suppose, from the title of this post, that you might have figured it out. Also, you might have guessed the name of my favorite song EVER. But let’s see what the Doorkeeper has in store for Jack.

He retracted into the ground. To tell the truth, I wasn’t sorry that he hadn’t invited me in. The aura of the place was really getting to me, and it was a relief backing away even a few steps. But the anticipation of traveling inside an Afterward would sustain me for a long time, until—as Captain Picard of the Enterprise would say—I could finally “make it so.”

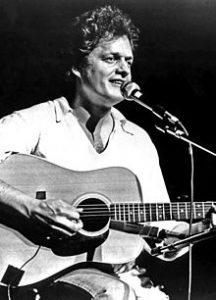

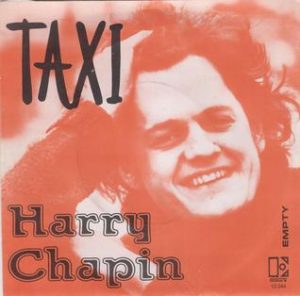

Harry Chapin, c. 1980

I was sitting on the bench and trying to figure out what the Doorkeeper had meant, listening to Del Shannon’s “Runaway” become Jim Croce’s “Time in a Bottle.” A figure appeared on the other side of the “door,” hesitated a moment, then stepped into the waiting area. Seeing him, I understood.

“Hello, Jack,” Harry Chapin said.

“Hi, Harry,” I replied, wondering if my voice could be heard.

He pointed at the Nishiki. “Hey, nice bike.”

“Thank you.”

Harry Chapin sat down next to me. Maybe I should’ve stood, but my legs probably would have buckled. He looked the same as I always remembered him. either on television or the live concerts that I’d been to, a few in New York during the seventies, before I left, the last in California—shortly before his death in a traffic accident in the summer of 1981. A head of hair that had not been worked on by Vidal Sassoon; the benevolent face with the dreamer’s smile that occasionally took the form of an impish grin. A flowered shirt, a pair of white slacks; no sequins, no glitz. An ordinary Joe who wouldn’t warrant a second glance if he sat next to you on the subway.

But such a profound effect on my life, and the lives of so many people, not only through his music, but in other ways.

But such a profound effect on my life, and the lives of so many people, not only through his music, but in other ways.

“So you heard what I was thinking,” I said.

Harry grinned. “Well, heard, felt, something like that. And since you were in the neighborhood, I thought it’d be nice if you…dropped in. You being the first Earther to ride the Ultimate Bike Path and all.”

This self-described “Third-rate folk/rock singer of long, wordy songs,” who once did a nearly six-minute ditty about thirty thousand pounds of bananas, didn’t have his den walls filled with platinum albums or gold singles. Ask the average person today to name two of Harry Chapin’s songs and they probably could, but not much more. One choice would likely be “Taxi,” his first biggie, which had nothing to do with Danny DeVito or Christopher Lloyd.

The other, without a doubt, would be “Cat’s in the Cradle.”

The song came out in 1974, and I fell in love with the simple lyrics. You know the story, how the father is so busy all the time that he’s never around for his son, but the undaunted kid really thinks Dad is cool and vows to be just like him when he grows up. At the end of the song, Dad is old and retired, and he asks the son to come and visit, but now the son is too busy, and he’s really sorry and all… And the old man, way too late, realizes his son had turned out just like him.

The song came out in 1974, and I fell in love with the simple lyrics. You know the story, how the father is so busy all the time that he’s never around for his son, but the undaunted kid really thinks Dad is cool and vows to be just like him when he grows up. At the end of the song, Dad is old and retired, and he asks the son to come and visit, but now the son is too busy, and he’s really sorry and all… And the old man, way too late, realizes his son had turned out just like him.

After my father died, “Cat’s in the Cradle” took on a whole new meaning.

And after Harry Chapin died… I could never again hear that song without getting choked up.

Here are two “Cat’s in the Cradle” incidents. The first happened in the early eighties, after Harry’s death, when I was still married to Carol. Back then I was as interested in religion as I am now, which is to say hardly at all. Carol, who had made a study of the world’s religions, had a secular curiosity, even though her upbringing as a Catholic had been more intense. So in an attempt to share her interests, I would go along to services in everything from the Presbyterian Church to the synagogue to the Self-Realization Fellowship.

I’ll never forget one Yom Kippur service, when this rabbi, a young and rather “hip” guy, read a “poem” to the worshipers. It was Harry Chapin’s “Cat’s in the Cradle.” He didn’t sing the words, didn’t even recite the chorus once, just the meat of it. Looking around, I realized from their smiles and nods that about half the people knew what was going on. Even so, they were as riveted as the others by the words, and when he got to the end, there were gasps. I swear. The words affected the congregation, and me too, even though I’d heard them a thousand times. I vowed that when I had kids, I’d never be invisible to them.

A couple of years later, I was in what they call the black depths of despair (which sounds like prosaic bullshit). The marriage to Carol was ending; the job sucked. My body was going the way of Jabba the Hutt. And on this one morning, on the anniversary of my father’s death, I was crawling along in early-morning traffic headed toward the aforementioned shitty job…when “Cat’s in the Cradle” came on the radio. With everything else on my mind, I also thought about Harry Chapin.

A couple of years later, I was in what they call the black depths of despair (which sounds like prosaic bullshit). The marriage to Carol was ending; the job sucked. My body was going the way of Jabba the Hutt. And on this one morning, on the anniversary of my father’s death, I was crawling along in early-morning traffic headed toward the aforementioned shitty job…when “Cat’s in the Cradle” came on the radio. With everything else on my mind, I also thought about Harry Chapin.

I had to pull out of the traffic for a while until I could stop crying.

Now, lest you think I bawl like a baby at the drop of a sombrero, I can probably count on one hand all the times I’ve done so in the past twenty years. You just happen to know two of those times, that’s all.

“Thanks for thinking about me that way, Jack,” Harry said.

Oh, yeah. I forgot he could hear everything I had rattling around in my brain. “Thank you, Harry.” He held out his hand. I looked at him. “Is it…all right?”

“Try it.”

I shook Harry Chapin’s hand. His grip was firm. I held it for a moment.

Then, what the hell, I hugged the guy. And he hugged me back.

“I have to go now, Jack,” he said.

“You do? But…you just got here.”

“We can only stay in the waiting area for a brief time.”

I hadn’t hardly said anything at all to this man, who had given half his concert earnings to combat world hunger and who had raised millions more by noodging other performers, politicians, and the like into doing something about it. I hadn’t told him how much a lesser-known “story song” of his, “Shooting Star,” meant to all the creative and weird people of the world, like me. I hadn’t asked him anything about what it was like in the Afterward, a place that both terrified and beckoned me.

I hadn’t hardly said anything at all to this man, who had given half his concert earnings to combat world hunger and who had raised millions more by noodging other performers, politicians, and the like into doing something about it. I hadn’t told him how much a lesser-known “story song” of his, “Shooting Star,” meant to all the creative and weird people of the world, like me. I hadn’t asked him anything about what it was like in the Afterward, a place that both terrified and beckoned me.

“There’ll be another time for us to discuss all of it, Jack,” Harry said, gesturing toward the opening. “It’s not so terrifying in the Afterward, not when you know how to get around. I’ll enjoy showing you through this one.”

Harry Forster Chapin, 1942-1981, waved to me, stepped into the Rock-and-Roll Afterward, and was gone.

I had followed him across three quarters of the waiting area. The music was still playing. Roy Orbison’s “In Dreams” became Jim Morrison’s “Light My Fire,” which became John Lennon’s “Give Peace a Chance.”

The Rock-and-Roll Afterward fell silent.

I knew that Harry was going to say good-bye to me with a song. I prepared myself for “Cat’s in the Cradle,” or “Shooting Star,” or maybe “Remember When the Music.”

The one he chose, bless him, was “30,000 Pounds of Bananas.”

Is that personal enough for you? This is one reason why writing is so cathartic.