Dybbuk, by Ephraim Moshe Lilien

A Jewish demon? Who knew! Yes, according to Jewish mythology a dybbuk is a ghostly, troubled spirit—most often the wandering soul of a deceased person—that possesses the body of a living person. (Though any living entity works, even a bug or a beagle, their host of choice is primarily a human.) In biblical times they were called ruchim, the Hebrew word for “spirit.” Not until the sixteenth century did the word “dybbuk” appear. It is a Yiddish version of an abbreviated Hebrew phrase that translates to “clinging spirit.” Apparently, when these spirits cling to a host, they’re not too inclined to let go.

Though stories vary, most portray a dybbuk as a disembodied spirit that, for whatever reason, is unable to pass on to the afterlife. Perhaps it wronged someone in its recent life and is unable to move on while it still has unfinished business. But if it truly was an evil person, it may be trying hard to avoid the inevitable punishment of the afterlife—the Hell realms or whatever.

In Jewish orthodoxy, those most susceptible to possession by a dybbuk are women (what else is new) or people living in a house where the mezuzah on the doorpost is askew or otherwise neglected. (A mezuzah is a vessel for small pieces of parchment that contain biblical passages from Deuteronomy.) That means the people living there are not particularly religious, or spiritual. Seems kind of extreme for a demonic possession, but what do I know…

So how do you get rid of a dybbuk? This brings us to the ever-popular concept of exorcism. For starters, a pious man needs to perform the exorcism. Usually that would be a rabbi, but I imagine any godly person will do. Some accounts say that this man should be assisted by an angel or a beneficent spirit. A synagogue seems a likely venue, though it does not necessarily have to be done there. Other accounts insist that it be performed before a minyan, a gathering of ten Jewish adults. It is especially helpful to learn the dybbuk’s name, which allows the exorcist to take better command of it. Also useful: learning why the spirit has not been able to move on. A troubled but not particularly evil dybbuk will gladly share its tale of woe. A nasty one, however, will require a lot more effort on the part of the exorcist and his assistants. It may even have to be trapped and contained in some kind of vessel. (More on the Dybbuk Box shortly.)

THE DYBBUK IN POP CULTURE

A scene from The Dybbuk (1922 play).

Ignored for much of Jewish history, the dybbuk first came to light in a 1914 play by Salomon Ansky, called The Dybbuk. This later became a 1937 Yiddish language film. But wait—so says Hollywood—a Jewish DEMON that takes possession of unsuspecting people and makes them do nasty things? How could we not jump all over that! Which brings us to two movies of recent vintage that highlighted—as only Hollywood can show us—the dastardly doings of dual dybbuks.

In the 2009 horror flick, The Unborn, the writer posits that dybbuks have a strong connection to twins.  None of my research indicated this to be so, but that doesn’t mean anything. Seems that a young woman named Casey is having all kinds of weird visions, plus her eye pigmentation is changing, to which an eye specialist asks if she is a twin, as this change is common in twins. She says that she’s not, but later on she learns that her mom, who committed suicide years earlier, had twins in the womb. The boy was strangled by Casey’s umbilical cord.

None of my research indicated this to be so, but that doesn’t mean anything. Seems that a young woman named Casey is having all kinds of weird visions, plus her eye pigmentation is changing, to which an eye specialist asks if she is a twin, as this change is common in twins. She says that she’s not, but later on she learns that her mom, who committed suicide years earlier, had twins in the womb. The boy was strangled by Casey’s umbilical cord.

Casey’s research leads her to an old Jewish woman in a nursing home who turns out to be her grandmother. (I guess she adopted Casey’s mom, but it is not explained.) This woman and her twin brother were prisoners in Auschwitz. The brother died at the hands of Nazi experiments but “returned” to life two days later. Knowing it was not her brother but possession by a dybbuk, she killed him and drove the spirit out. It has haunted the family ever since (the reason for mom’s suicide), and now it is Casey’s turn.

Lots of nasty stuff happens during this film in typical Hollywood gross-out style, but ultimately Casey enlists the help of a rabbi, played by Gary Oldman (yes, Sirius Black!), to exorcise the dybbuk. His method of exorcism: a minyan, and prayers…

I won’t tell you what happens. Despite the role of the dybbuk and the methods in fighting it, The Unborn is pretty standard horror movie fare. Its reviews were poor, but what the heck, it made a potload of money for its creators.

Somewhat better was the 2012 film, The Possession. But before I talk about it, some details about the fascinating story of the Dybbuk Box are in order.

THE DYBBUK BOX

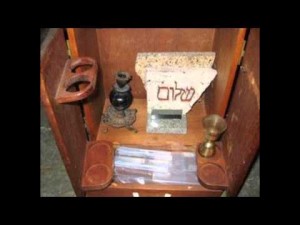

You may have heard about the Dybbuk Box (or Dibbuk Box), a haunted wine cabinet that appeared on eBay a little over a decade ago. For greater details check out the Dibbuk Box website. Short version: the box came to America with a Holocaust survivor named Havela, who purchased it in Spain. An antiques dealer in Portland OR, Kevin Mannis, bought it at an estate sale in 2001 after Havela died. The woman’s family seemed overly thrilled to be rid of it. They told Mannis that, according to grandma, a dybbuk had been trapped in it years earlier.

The Dybbuk Box, opened.

After a series of bizarre happenings at his shop, Mannis opened the box and discovered a number of odd, assorted items inside, including a lock of hair and a statue with the Hebrew word “Shalom” carved in it. He also found Hebrew words carved on the back of the cabinet. Later on he would reseal the box and give it to his mother as a birthday gift. That same day she would suffer a stroke. When she could eventually write, she begged him to get rid of the box.

And so the box went up on eBay, along with a long disclaimer by Mannis detailing the gruesome history of the Dybbuk Box. Apparently there is a culture that deals in strange objects such as this. A college student in Missouri purchased it, but after his own misfortunes he sold it to Jason Haxton, a museum director in Missouri. Haxton also opened the resealed box, and his misfortunes began. After consulting with some rabbis he again sealed the box and hid it away from his family. It has remained quiet since then.

THE POSSESSION

No less a luminary than San Raimi (The Evil Dead, Spiderman 3, The Grudge) took an interest in the story of the Dybbuk Box, which led to him producing The Possession—“based on a true story,” Hollywood-style, of course. In it, a young girl named Em buys an ancient box at a yard sale, even though a dying old woman inside the house tries to warn her away. Her dad, Clyde, cannot open it with tools, but later on she finds a trick latch, and the dybbuk is released. The sweet little kid becomes a holy terror, even causing the death of a schoolteacher, among other things.

The distraught Clyde shows the box to a college professor, who says that it is a dybbuk box nearly a hundred years old, and that it was used to contain a demon. Read a portion from the Torah, he says, and  it may be driven out. Clyde tries, but the dybbuk, now in full possession of the girl, destroys the pages. Clyde then enlists the help of a Chasidic tzaddik—a man of great piety—to lead a forced ritual exorcism. The results are amazing to watch.

it may be driven out. Clyde tries, but the dybbuk, now in full possession of the girl, destroys the pages. Clyde then enlists the help of a Chasidic tzaddik—a man of great piety—to lead a forced ritual exorcism. The results are amazing to watch.

With one exception, I won’t tell you much more than this. While this film had its share of Hollywood horror hokum, it also offered some truly unsettling moments without the requisite over-the-top blood and guts. The one scene that really creeped me out: young Em, having been hospitalized with a seizure, is undergoing an MRI. As everyone watches the monitor, the dybbuk’s face appears—next to her heart. Eeyew! Needless to say, this one made a potload of money as well.

Spirits that cannot pass on over to the next world appear to be a common theme among a great many cultures and ethnicities. So discovering this in Jewish folklore should not come as any surprise.