Now there are two words that don’t seem to belong together. California Sun? A natural. California Dreaming? The Mamas and the Papas sang about it. California Girls? Well, yeah.

“Genocide” is not a pretty word. According to Merriam-Webster, it is “…the deliberate and systematic destruction of  a racial, political, or cultural group.” Hearing it, you might think of Nazi Germany, or Bosnia, or Rwanda. Not California, original home of the happiest place on the planet, land of fruits and nuts, the capital of Make Believe.

a racial, political, or cultural group.” Hearing it, you might think of Nazi Germany, or Bosnia, or Rwanda. Not California, original home of the happiest place on the planet, land of fruits and nuts, the capital of Make Believe.

But if you want a jolt, go ahead and plug “California Genocide” into Google or any other search engine. I did exactly that in researching background information for my new novel, The Burning Ground. The many websites addressing the annihilation of the state’s indigenous native population will prove a sobering eye opener.

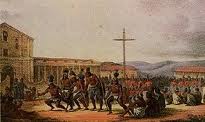

Prior to the arrival of Spanish missionaries and other Europeans by the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, California’s indigenous native population was estimated at between 300,000 and 700,000. Father Junipero Serra, a Spanish missionary, encountered Indians as he built the first of many missions that would eventually  extend from San Diego to San Francisco. He would write, “When I saw their general behavior, their pleasing ways and engaging manners, my heart was broken to think that they were still deprived of the light of the Holy Gospel.” He then tried to convert all the Indians he encountered to Christianity.

extend from San Diego to San Francisco. He would write, “When I saw their general behavior, their pleasing ways and engaging manners, my heart was broken to think that they were still deprived of the light of the Holy Gospel.” He then tried to convert all the Indians he encountered to Christianity.

With the spread of the “white man’s diseases” such as malaria, cholera and smallpox, with enslavement, imprisonment, forced conversion, beatings and wars—many Indians fought to preserve their heritage—the number had  decreased to approximately 150,000 by 1848, the year that gold was discovered at Sutter’s Mill in northern California. This brought the world to California, and along with it a new round of genocide. Northern California’s many small tribes, including the Maidu in the Sierra Nevada foothills and surrounding areas, were decimated; some of them all but ceased to exist.

decreased to approximately 150,000 by 1848, the year that gold was discovered at Sutter’s Mill in northern California. This brought the world to California, and along with it a new round of genocide. Northern California’s many small tribes, including the Maidu in the Sierra Nevada foothills and surrounding areas, were decimated; some of them all but ceased to exist.

In The Burning Ground my three lead protagonists, Barry Cordell, Dana Bowen, and Billy Grider, are listening to an elderly Native American named Monroe Putnam as he tells the story of his Maidu ancestors. Here is the scene:

The old man nodded then continued with his slow, deliberate narrative: “This gold filled the rivers, the streams, the hillsides and the valleys. My people had always known of it, but it meant nothing to them. More valuable were the dentalia and haliotis shells made into necklace pendants, the Pomo disk beads, the obsidian stone, even the woven baskets. But to the white men, gold was their Great Spirit, their Earthmaker, and they came in great numbers to take it from here. They killed many of those who you call Indians or Native  Americans—they called us Diggers!” He spat the word.

Americans—they called us Diggers!” He spat the word.

“Some of our people made friends with the whites and even helped them look for gold in trade for clothes and other trinkets of little value, and—the whiskey! And some of the women did things…” He glanced at Billy and chose not finish the thought.

“All of this is known. It is history. One of your politicians at the time wrote a report to the Secretary of State and called the people ‘degraded objects of filth and idleness.’ Some of the smallest tribes became no more. This was—genocide, your word for it. They were shot down for no reason at all. They fell to the white skins’ diseases, and to the terrible firewater…”

The old man paused for a moment, trembling. Billy patted his arm gently but said nothing.

In 1851 the governor of California, Peter Burnett, weighed in on the situation: “A war of extermination will continue to be waged between the two races until the Indian race becomes extinct.”

By 1870 the indigenous native population of California had fallen to 31,000. As I wrote in my Author Introduction, What you’ll read in chapter one of The Burning Ground—ghostly spirits notwithstanding—is not entirely fiction.

“SWORDS” UPDATE: I’m nearly done with the revisions for The Sons of Ornon, one of my early Sword & Sorcery novels (first published by Zebra Books as The Twentieth Son of Ornon). I can safely say that it will be out sometime in March under my own imprint, Atoris Press. As embarrassing as some of my old novels were to me, Ornon proved a pleasant surprise. I fixed the heavy-handed, “gag-me” writing but retained the story, which I think you’ll find fun and exciting. You’ll hear more about it in upcoming posts. Meantime, have a look at the prototype cover (it won’t be the final) that I’m working on with my excellent graphic designer, Karen Phillips. (Karen lives in the aptly—or not—named town of Cool, California, which just happens to be on the way to The Burning Ground’s fictional town of Lodestar.)

Wow. So I guess ‘california genocide’ isn’t an oxymoron after all. The Burning Ground sounds awesome. Eager to learn more about The Sons of Ornon, too.

Mike,

When you first spoke of California Genocide I did as you suggested (plugged it into Google) and ended up reading for hours. The sadness at being reminded of the true history of this State, as well as many other places, still has not left me. It is a perfect example of how “accepted history” is written by the victors. I beleive it takes courage to include such realities in your stories, as I am sure there are some people who would shy away from them for that reason alone.

As for a different type of courage…I’m dying to see just one example of what you considered “gag me” writing, before and after. Care to share?

That would take too long for a blog post, Kate, but I promise I’ll get back to you on it. 🙂