The PS General Slocum

The 9/11 terrorist attack on New York in 2001 was—and still is—the city’s worst disaster involving loss of life. Prior to that, the dubious record was held by an incident that occurred nearly a century earlier. This is the story of the paddle steamer General Slocum and its ill-fated voyage in 1904.

A PERFECT STORM

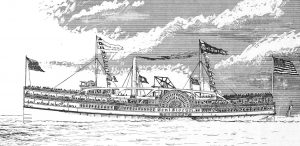

On a beautiful June morning over 1,300 folks—mostly women and children—from St. Marks Evangelical Lutheran Church gathered at the Third Street pier in Manhattan for a day of sun, fun, and food. They would board the sidewheel passenger steamboat, PS General Slocum, for a cruise up the East River, then into the Long Island Sound, finally disembarking at a picnic site along Eaton’s Neck.

The Slocum, built in 1891, had its share of baggage. She had run aground a number of times, struck a sandbar once, and collided with a couple of other vessels over its thirteen-year life. The most recent incident occurred only two years earlier. Still, the revelers were undeterred as the Slocum, under the command of Capt. William Van Schaick, sailed off at 9:30 a.m.

The Slocum, built in 1891, had its share of baggage. She had run aground a number of times, struck a sandbar once, and collided with a couple of other vessels over its thirteen-year life. The most recent incident occurred only two years earlier. Still, the revelers were undeterred as the Slocum, under the command of Capt. William Van Schaick, sailed off at 9:30 a.m.

Half an hour later a fire started in the forward cabin as the vessel passed E. 90th St., possibly the result of a discarded cigarette. A 12-year-old boy first tried to warn the captain, but Van Schaick blew the kid off. By the time he realized that the boy was telling the truth, the blaze had grown to dangerous proportions. He ordered “full speed ahead” to reach North Brother Island, where they could beach the vessel and off-load the passengers.

As the crew prepared to fight the blaze—even though they had not trained for a fire that year—they made some frightening discoveries. The fire hose had rotted, and it burst in a number of places as they tried to use it. The lifeboats, which they could have utilized to begin evacuating the passengers, were tied down and inaccessible. Life preservers fell apart in their hands. This was a perfect storm for an unimaginable disaster.

As the crew prepared to fight the blaze—even though they had not trained for a fire that year—they made some frightening discoveries. The fire hose had rotted, and it burst in a number of places as they tried to use it. The lifeboats, which they could have utilized to begin evacuating the passengers, were tied down and inaccessible. Life preservers fell apart in their hands. This was a perfect storm for an unimaginable disaster.

“A SPECTACLE OF HORROR…”

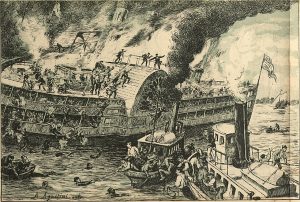

While Van Schaick could have run the Slocum aground anywhere, he continued on course for North Brother Island. Headwinds fanned the flames and turned the vessel into an inferno. Panicked mothers began putting life jackets on their children and tossing them into the river, only to see them sink. Many jumped in after them, but the heavy clothing worn by women of that era, as well as the inability of most to swim, caused them to drown.

By the time the vessel beached on the island, it was engulfed by flames. Passengers continued to leap into the water, most drowning, others killed by the paddles, which continued to turn. As many as 500 people died after the Slocum was beached.

Many bodies floated up on the shore of North Brother Island.

Two tugboats soon arrived and rescued as many as 300 people, along with the help of staff and patients from a hospital located on the island. Still, over 1,000 people either drowned, burned to death, or were chopped up by the paddles. A reporter of the day referred to the incident as “A spectacle of horror beyond all words.”

Capt. Van Schaick, who lost an eye during the incident, deserted the Slocum as soon as the tugboats arrived. Ultimately, he would be one of eight people indicted by a federal grand jury, the others being officers of the company that built the vessel. Van Schaick was found guilty of criminal negligence for failing to maintain the equipment or supervise fire drills. He was sentenced to ten years, paroled after three-and-a-half years. The company received a slap on the wrist: a small fine. Some things never change.

As for the PS General Slocum: over an hour after beaching on North Brother Island it broke free and drifted about a mile, finally sinking just off The Bronx. It was soon salvaged, renamed the Maryland, and converted into a barge. In 1909, while carrying a load of coal, it sank in the Atlantic Ocean off the coast of New Jersey. It was not recovered—likely for the better.

As a young man I asked why the rule books say we do certain things, why we practice these same drills time and time again, why we inspect equipment seemingly every other day, why we do maintenance on equipment that doesn’t see much use. A chain-smoking old Senior Chief answered: “Every one of those rules is written in blood.”

People say writers are a pessimistic bunch, but a hundred years ago, today, or a hundred years from now, greed and arrogance guarantee us tragedies that are worse than the most lurid fiction.

How true, Mark. And it is more evident these days than ever before.