I’ve run this post before. But with our beleaguered country, as well as the rest of the world, undergoing a much-needed reboot, I felt that the time was right to run it again. The Number People, although presented in fictional format, is a true story right out of my childhood in The Bronx.

I had forgotten about the Crazy Lady, a figure out of my past. No surprise, as it was over sixty years ago, and she played a small part in my life. But writing a recent post—especially the last part of it, about one of my fictional characters traveling through time and running into Hitler as a child—made me think of her again. And that reminded me of a story that I wrote a long time ago, in which the Crazy Lady also appeared.

So okay, I’m going to dwell on this for one more post, and afterward I swear I’ll get back to giant flying lizards, time travel, nightmares, barbarians, mutated cockroaches, bad movies, and other good stuff like that. For now, here is my story, The Number People.

My name is Benjamin. When I was a boy growing up in the city, it seemed as if they were everywhere. All around our neighborhood, you could always see the Number People. They lived quietly, walked swiftly, and hardly ever smiled.

Some of my friends used to tease the Number People; shout at them, or run in front of them when they didn’t expect it. Most of the Number People would yell at the boys; others would look scared and say nothing, just hurry away.

I always wondered about the Number People. They acted strange, as if they were keeping a secret or something. Like always looking at the ground when they walked, or jumping up suddenly when there was a noise. It didn’t even have to be loud; just a garbage truck bumping along would do it. And they looked so worried.

Mostly, I just watched the Number People and left them alone. But sometimes, when I was with my friends, I forgot, or thought that I should do the same dumb things they did.

It was David who first called them the Number People. He didn’t think they were too smart. “They can’t remember their own phone numbers!” he said. “Why else would they have to write them on their arms?”

It was David who first called them the Number People. He didn’t think they were too smart. “They can’t remember their own phone numbers!” he said. “Why else would they have to write them on their arms?”

We all laughed. Barry suggested, “Maybe they write down test answers, like we do sometimes.”

“But they’re grown-ups,” David argued. “They couldn’t have had those on for so many years!”

“Maybe they never take baths,” Alan said. We laughed even harder.

Sometimes the Number People told our parents on us. Barry, David, and Alan were always punished. I couldn’t find any of them to play with for days. My mother never punished me—not like the other boys, anyway. But I always knew when one of the Number People had talked to her. It was that silent look she gave me when I got home from school, the one that said, You know what you did, and so do I. And son, am I disappointed in you! I thought it was worse than any punishment. After that we would leave the Number People alone for a while; but sooner or later it would start again.

We had names for some of the Number People. Creepy Cohen and his wife owned the grocery. They used to hate it when any of us kids came in. So did Grumpy Adler at the candy store.

Skinny Levine, who lived in a small room behind the school, did odd jobs in the neighborhood. He was tall and bony. We didn’t think the man even knew what food was! Alan liked to tease him the best.

But most of all, there was the Crazy Lady. She lived in the next building and wore this old blue coat, all the time! It didn’t even matter if it was the middle of summer. We’d never seen her numbers, but Barry said he knew she was one of them, for sure.

The Crazy Lady was real old; to us, anyway. She was kind of bent over when she walked, and always pulled this wire cart. Sometimes there was a small sack of groceries inside; but there was always the bag, a big cloth thing with a handle, probably her purse. We tried to imagine all the witchy things inside it, like poison apples, maybe, or another kid, to take home and fatten up for her roasting pot!

She looked angry, the Crazy Lady, and always seemed to be talking to herself. Whenever she saw us she would come at us and yell things, even when we weren’t doing anything. We always got away; but we never stopped watching out for her.

It was this one afternoon that changed everything. Outside, it rained hard. Alan and Barry were away at music lessons. David was sick.

It was this one afternoon that changed everything. Outside, it rained hard. Alan and Barry were away at music lessons. David was sick.

I was bored. With homework done, there was nothing else I felt like doing. Looking down from our third-floor window, I saw Creepy Cohen’s wife hurry out of the grocery store. Soon she was up the stairs, banging on our door. She told my mother that Skinny Levine had died. Then she turned around and left.

My mother just stood there for a minute, then sat down. I stared at her, not understanding why she looked so sad. Skinny Levine was always by himself; always alone. I didn’t even think she knew him.

She had me sit on the sofa next to her and held me tightly. It was something she only did when I was upset, or when she had something important to tell me.

“Nathan Levine just died,” she said.

“Oh. He must’ve been pretty old, huh?” I said.

“Nathan Levine was younger than your papa. No, Benny, it wasn’t because of that.”

“Why then, Mama? Was he sick?”

“Sort of. But not the kind of sick like when you stay home from school.”

“Mama, what are you talking about?” I asked. Then, not quite sure of what I was saying: “I know! It has something to do with the numbers, doesn’t it? Skinny Levine was one of the Number People! What does it mean, Mama? Are all of the Number People going to die?”

“Number People, Benny?” she said. “I don’t know—”

“On the arms, Mama! He had one. The others in the neighborhood; so many…”

She smiled, but kind of sadly. It surprised me. Nodding, she said, “Your friends make fun of those with the numbers; sometimes, you do. I know it is because you are young and don’t understand. You are all good boys.

“Even though you are only nine, Benny, I thought that soon you would ask. You want to know, don’t you? About the Number People?”

“Oh yes, Mama!”

“Then I will try to help you understand. Once, these people lived in faraway countries like Poland, Germany, Austria, Hungary.”

She looked away for a minute and said softly, “It wasn’t so many years ago, actually.”

“Why did they all come here?” I asked. “Did they want to leave their homes?”

“None of them wanted that. Nor did they leave and come here first. There was someplace else they went to before that. People, bad people, made them go there.”

“Who were they?”

“They were people who hated everyone who was…different. They called themselves Nazis. They wanted to be kings of the world, so they made war; first against small countries, then everyone, including America.

“Mostly, they hated the Jewish people and wanted to kill them all. So they first took away everything the Jewish people owned, and made them leave their homes.”

My mother stopped talking and took out a handkerchief. “Where did they go?” I asked.

Auschwitz gate: “Work sets you free.”

“They were taken to dark, ugly places with high fences all around. The fences were electric and would burn if people touched them, and had sharp barbed wires that cut. Concentration camps, they were called. Camps! Many believed they were going to someplace nice. It was to these camps that they sent whole families with children, and old people too.”

I wasn’t sure if I wanted to hear more. But I had to know.

“What happened to the people there, Mama?”

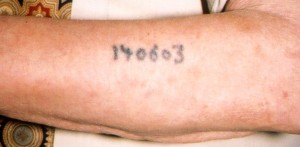

“Many were killed on the day they arrived. The others were taken to a room, where numbers were burned into their arms.”

“Like cattle are branded in the western movies?” I asked.

She nodded. “Something like that. It was so the Nazis would always know who their prisoners were. After that the people were kept in cold, crowded rooms. They had few clothes to wear, and never enough to eat. Every day many were chosen to die, so that there would be room for new people. But others were made to work from early morning until late at night, and after a while they too would die from being so weak or hungry.”

What my mother was saying seemed impossible to believe. “Even the children had to go there and work?” I asked.

She nodded, saying, “Ira Weiss across the street is one of your Number People. He looks much older but is only twenty-three. When they took him there he was just ten, not much older than you are now.”

She hugged me again. Afraid to hear an answer, I said, “A lot of people died in these camps, didn’t they?”

“What do you think a lot is, Benny?”

“Hundreds, or thousands?”

“At least six million of the Jewish people in Europe were killed by the Nazis. But they killed others too, maybe another four million, who were not Jewish. That’s more people, Benny, than are here in the whole city of New York!”

I remember saying something dumb, I think, like, “Why would anyone want to hurt so many people?” Then I asked, “But how did they make it out? How could they?”

“Because,” my mother said, “they remembered how much better things had been before then, how they had loved to be alive, and they hoped that, one day, it would again be the same. They remembered the holidays, and on those holidays prayed together, shared the little bit of food, sang songs if the Nazis were not listening. It was, I like to feel, because they were so full of hope, and because they never stopped caring about themselves, and one another. This is why I am so sad for Nathan Levine.”

“What do you mean, Mama?”

“When Nathan Levine was in the concentration camp, he became friends with a man. Once, this man was very sick and almost died. Nathan Levine brought him extra food, until the man was better. This man, Benny…was your papa.”

“When Nathan Levine was in the concentration camp, he became friends with a man. Once, this man was very sick and almost died. Nathan Levine brought him extra food, until the man was better. This man, Benny…was your papa.”

I began to cry, and she held me more tightly until I could stop. She had always been able to make the hurts go away. I was so glad she was there.

“Papa?” I sobbed. “But the numbers—! I never saw them!”

“They were not as deep as so many others, and the dark hair on Papa’s arms covers them,” my mother explained. “He has always been glad for this.”

I stopped crying and looked at her. “The lady in the next building. With the blue coat…”

“Whom you boys call the Crazy Lady,” she said. “Yes, David’s mother told me. Her name is Mrs. Berkowitz. She was in one of the camps. Her husband, three children, and others of her family were there too. None of them came out.”

The next day my parents took me to Nathan Levine’s funeral. I had asked to go. Not many people came; most who did wore the numbers.

Later, I was with David, Barry, and Alan again. But I remember that it was sort of different. The things they were saying, or wanted to do, didn’t seem so important anymore. I knew that I had grown up a lot.

I thought about telling them. But would they believe me? Maybe it was better for their parents to do it. In our busy neighborhood, with the Number People all around, it wouldn’t take long for them to know that something was different…about me.

It happened sooner than I thought. Mrs. Berkowitz, as always pulling her cart, was turning the corner. Seeing us, she frowned and walked more quickly, waving a fist.

“Hey, it’s the Crazy Lady!” Alan said, jumping off the stoop.

The others got up. I stood in front of them. “No!” I shouted. “Not today. Not anymore.”

They laughed, but they listened. Barry shook his head and exclaimed, “What’s wrong with you, Benny? You’re weirder than she is! Hey, look, she’s close. Let’s get out of here!”

They ran; I didn’t. Turning, I waited for Mrs. Berkowitz. I was scared; but I wouldn’t leave.

“Rotten kids!” Mrs. Berkowitz yelled. “I’ll get you! You’ll see, I’ll get you all!”

She stopped when she saw me just standing there. The frown left her face. For a moment I thought she looked scared. I met her eyes and tried to smile.

“I’m…sorry,” I said.

I can’t remember what Mrs. Berkowitz did then. I think she nodded, sort of. Anyway, she looked different when she hurried past me with the cart. It was a sad look, but not so angry anymore.

David found out about the Number People, too. I don’t know about Alan and Barry because they moved out of the neighborhood and I lost track of them.

As I grew older I learned more about those people, and the terrible time that came to be known as the Holocaust. Papa would never talk about it, not until a lot of years had passed. Few of the Number People talked about it. But finally, some of them did. And even though the memories of what they had been through, of what they had seen, were so painful, it made things better to share them with those who cared.

I felt glad when Papa talked. I wanted to take some of his hurt, so that I would always remember what had happened. Papa was strong and brave, and I sure loved him.

Now I’m a father, and it’s my turn to tell my children about the courage of the Number People. It is what we learn from these lessons of the past that can help us build a better, more understanding world.