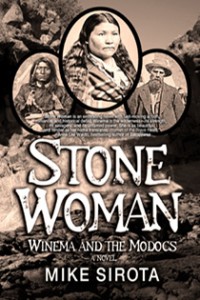

When writing historical novels based on true events, the challenge is to not make the scenes read like dry, academic research for a thesis. My award-winning historical novel, Stone Woman: Winema and the Modocs, offers many examples of how (hopefully) not to bore readers. I will present some scenes to illustrate what I mean.

WHAT IS THE CONFLICT?

As it is with most stories about Native Americans, the conflict emerges from their desperate struggles to protect their culture, their way of life, from white America as Manifest Destiny drives it westward. It was no different for the small Modoc tribe of southern Oregon/northern California. In fact, their story serves as a microcosm for just about all the tribes of North America, whatever their size.

As it is with most stories about Native Americans, the conflict emerges from their desperate struggles to protect their culture, their way of life, from white America as Manifest Destiny drives it westward. It was no different for the small Modoc tribe of southern Oregon/northern California. In fact, their story serves as a microcosm for just about all the tribes of North America, whatever their size.

Much of the story is presented through the eyes of Winema, a Modoc woman who is destined to marry a white man. As early as chapter one the conflict is laid out in what I believe is a unique setting. “Winema” will not be given that name, which translates to “Woman of the Brave Heart,” till she performs a heroic deed later in the story. As a young girl she is called Nanooktowa, the “Strange Child,” given her independence and strong will. In the opening scene she has journeyed to a particular spot in the Link River called the Sacred Place. There, under certain conditions, a stone image representing Kumookumts, the Creator, can be seen in the middle of the river. Nanooktowa has been there many times before to talk to the Creator. Now, after some “small talk,” she has something else to say. Here is the scene:

“Our Father, I am sorry, you do not want to be troubled with such foolishness! Let us speak of the basdin. I suppose you are keeping an eye on them. More and more they were the subjects of conversations in the winter temescals. I have not yet seen one; I do not think I ever want to. Some of our men wear their clothes and carry their awful guns. But they have gotten these from the trading councils in the far-off northern place called The Dalles, not from the ones who have come to our land. They have killed some of the People and we some of them, although the Lagi has said we should avoid them. My father agrees with our chief.

“But now there is something else. The shiny metal, the gold, has brought more of them here, and they stay. There is even word of a white man’s village to the southwest, toward the Ieka mountain. Please, Kumookumts, let them find what they want, so they may leave the Smiles of God and go back where they came from. As my cousin Kientpoos has said, ‘The People do not need this distraction in their lives.’”

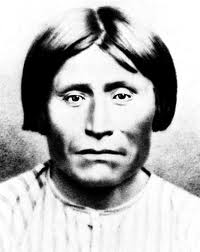

Kientpoos, also called Captain Jack

A CHILD OF DREAMS

In chapter three, titled “The White Hand,” I present a scene in the Modocs’ village after Nanooktowa returns from the Sacred Place. It is designed to illustrate the day-to-day activities of the tribe, though in this context there is an undercurrent of concern. Then, the village becomes the site of frenetic movement as the people learn that the kyog (shaman) has had a dream, a significant occurrence. Nanooktowa joins the rest of the tribe at the shaman’s lodge. Here is the scene:

The Lagi gestured for silence. For a few moments the frail kyog, whose eyes were shut, rocked from side to side. The cracked lips then parted. A deep imposing voice carried through the village.

“I walked in the new grass of a mountain meadow,” he began. “Subbas dominated an endless blue sky, warming my old bones. Children splashed in a stream, where fish of great size leaped. Deer and longhorn sheep grazed nearby, and eagles swooped low to hear the sound that blanketed the meadow, the sweet words of the Kamisnostinto, the ancient love song.

“Then, it changed. A distant thunder rose, drowning the song. The animals fled but the thunder was even louder than before, and many of them fell dead. Fish leaped to the banks, thrashed, then also died. Nearby, our children huddled together in fear, their cries as one.”

“No, no!” an old woman moaned, and eyes turned toward her. But the kyog seemed not to hear as he went on with his vision.

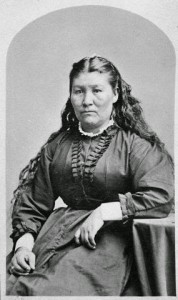

Winema, Modoc Woman of the Brave Heart

“A cloud appeared from over the mountains, blacker than anything I had ever seen. It blotted the sky as it floated toward the children. Their wails became louder, rivaling the thunder. I wanted to run to them but could not move, for my legs had no feeling. Nor could I call out, for my voice was lost among the other sounds.

“Now there was no blue sky, and the meadow grass wilted. From the hovering darkness a great hand was thrust out, a white hand, and it seemed to be gesturing. One finger pointed toward the children.

“Another white hand emerged, then another, and more, and more, until they were too many to count. They reached down and one by one began to touch our children, whose cries ceased, as did the thunder. The children were affected differently: some died quick, silent deaths that were bloody and terrible, others groveled on the charred earth. As they crawled away their young bodies became gray, gnarled, and their eyes rolled back as trembling fingers clawed feebly through puddles of their drool. There were a few—only a few—who rose on strong legs, heads held high against the thousand white snakes squirming around them. But the thunder again sounded, and those who did not fall were crushed like insects by a rain of hands that shoved them to the ground. The white hands were lifted skyward, fists clenched, the blood of our children seeping between fingers. Finally they were withdrawn, until I could no longer see them. But the darkness remained, and I knew it would not go away.”

The tribe is freaked out by the kyog’s vision. No one is quite sure what it all means. Well, there is one who knows. Here is how the chapter ends:

The Modocs dispersed; soon the area around the kyog’s wickiup was deserted. Nanooktowa would have preferred walking home with her father, but he again left to be with the woman. Koalaka joined her family, leaving only Uleta. The boy remained mute during the brief walk. He, like the others, had been deeply affected by what they had just heard. He soon left, and she was glad, for her own mind reeled from the images planted there by the kyog.

The night passed in restless turning for the girl, because she was a child of dreams, and unlike the confused tribe she had an idea of what the dark vision meant.

As I have always said during my many years of teaching, truth is often stranger than fiction, but fiction can be far more compelling than truth. Remember that when you check out Stone Woman: Winema and the Modocs.