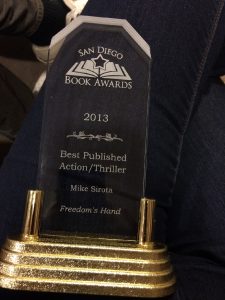

Just about four years ago I released my award-winning thriller, Freedom’s Hand. Here is my introductory blog post. Unfortunately, the book seems to have more relevance in this current climate of racism and intolerance.

Just like the name of my website professes, most people know me as a writer in genres such as sword & sorcery, sword & planet, horror, paranormal, fantasy, and science fiction. That is why my newly released novel, Freedom’s Hand, may come as a surprise, for it is none of the above. But given where a great deal of the story takes place—inside a concentration camp on American soil—it may prove more disturbing than any previous gore-fest I’ve written. Why? Because it HAS happened in the past. For real.

Just like the name of my website professes, most people know me as a writer in genres such as sword & sorcery, sword & planet, horror, paranormal, fantasy, and science fiction. That is why my newly released novel, Freedom’s Hand, may come as a surprise, for it is none of the above. But given where a great deal of the story takes place—inside a concentration camp on American soil—it may prove more disturbing than any previous gore-fest I’ve written. Why? Because it HAS happened in the past. For real.

As with many things, the actual creation of Freedom’s Hand has a history—in this case a long one. But before I get into that, let me offer a plot abstract, at least for the early scenes. The story opens in 1943 Poland with a teenager named Nathan Adler inside a crowded cattle car, one of many pulled by a locomotive on its way to oblivion. Nathan’s mother and young sister are with him. Eventually the train pulls into Auschwitz. Nathan, a sturdy young man, is taken aside to join a work detail. His mother, a cripple, is put on a line to the gas chamber. The sister, four years old, staggers about helplessly before being torn apart by guard dogs as Nathan watches.

The majority of the story takes place in 1994. A now elderly Nathan Adler, a widower, is on a summer driving vacation with his family: his daughter, Susan Lowe; her husband, David; and Heather, their eight year old, Nathan’s beloved granddaughter. Nightmares of the past still torment him, but he manages to deal with them.

Then, the nightmares become real once again as the family is kidnapped in Nevada by a white supremacist group called Freedom’s Hand. Thrown into a cramped, stifling compartment in the back of a church bus with other prisoners—mostly blacks and Mexicans—they are transported to a strange compound deep in the searing desert. While the others are incredulous, Nathan seems to know what is happening; he’s been there before.

Then, the nightmares become real once again as the family is kidnapped in Nevada by a white supremacist group called Freedom’s Hand. Thrown into a cramped, stifling compartment in the back of a church bus with other prisoners—mostly blacks and Mexicans—they are transported to a strange compound deep in the searing desert. While the others are incredulous, Nathan seems to know what is happening; he’s been there before.

The compound, enclosed by towering fences topped by barbed wire, is called LAGER—the German word for “camp.” Manned by an army of brown-shirted thugs, Lager is the brainchild of an enigmatic man who, early on, is known only as the Commander. This monster is dedicated to the systematic extermination of all minorities. His “technical advisor” is Unterscharfuhrer Heinz Kell, an old man now but once part of Nazi Germany’s Protection Squad, the SS, and a prison guard at Auschwitz. Kell had been a personal nemesis to the young Nathan, and their meeting now—fifty years later and a world away—is monumental…

Auschwitz gate: “Work sets you free.”

Just as I would hate to give away how this confrontation ends up, so am I loath to say much more about the story without revealing too many key plot points. David and Susan Lowe, as the main protagonists, must call upon courage that they would have thought unimaginable if they are to survive this Hell on Earth called Lager and save their family from the camp of swaggering monsters. The odds are seriously stacked against them.

I’ve written about human monsters before—think Bruno Leopold in Fire Dance—but the Commander presented a different kind of challenge and, in retrospect, became the most difficult character that I ever created. What makes a Hitler, or a Stalin, or a Pol Pot, or a Joseph Kony tick? These are heads that the average person doesn’t particularly want to delve into, but as a writer you have no choice—not if you want readers to believe that your characters could be motivated to engage in actions so heinous. So how does one do this?

In Freedom’s Hand I use a series of flashback scenes, spread out over many chapters, to show how a monster evolves. Preceding each flashback the Commander is usually talking to his second in command, a friend who addresses him as “Martin.” Over time we learn that Martin’s mother was the most famous actress of her era, his father one of the world’s richest men. We experience Martin as a boy, a teen, a young man, and so on, not only with tons of emotional baggage but also with incidents occurring at each stage that could spur some racial or religious intolerance and motivate hatred.

But enough motivation to make someone go out and erect a concentration camp in the desert of the American Southwest and dedicate a life to destroying human beings?

To accomplish this I truly had to separate Myself from Myself—from who and what I am, from all I believe—and become the mind and the voice of a monster. In a chapter titled “Revelation” the flashback scene has Martin as a young man. He has just graduated from a military academy and is staying with a friend in Chicago. The friend takes him to a rally in a suburban park, where a neo-Nazi group has challenged—and won—their right to free speech in court. (This is based on a number of true incidents.) The park is in a predominantly Jewish neighborhood, one where many Holocaust survivors live. They are out in force, as are many other Jewish and African American organizations, to protest the speech given by Robert Earle Wesley of the New Socialist Front. Martin is minimally interested, and because he hates crowds he really wishes that he were somewhere else—at first.

To accomplish this I truly had to separate Myself from Myself—from who and what I am, from all I believe—and become the mind and the voice of a monster. In a chapter titled “Revelation” the flashback scene has Martin as a young man. He has just graduated from a military academy and is staying with a friend in Chicago. The friend takes him to a rally in a suburban park, where a neo-Nazi group has challenged—and won—their right to free speech in court. (This is based on a number of true incidents.) The park is in a predominantly Jewish neighborhood, one where many Holocaust survivors live. They are out in force, as are many other Jewish and African American organizations, to protest the speech given by Robert Earle Wesley of the New Socialist Front. Martin is minimally interested, and because he hates crowds he really wishes that he were somewhere else—at first.

I modeled Wesley after George Lincoln Rockwell, an infamous American Nazi of the 1950s and ’60s. His rants against Jews and blacks were poisonous—and so was the one that I put in the mouth of Robert Earle Wesley. To this day I remain stunned that I could have ever written such words, or imagined such thoughts. But to make their stories work, writers sometimes have to step far out of their comfort zones. I mean, does Thomas Harris have his doctor for dinner with some fava beans and a nice Chianti? Does James Patterson enjoy some of the same simple pleasures as his greatest antagonist in the Alex Cross books? I think not; yet Hannibal Lecter and Kyle Craig are two of the most believable and chilling monsters in all of fiction.

I won’t share any of Wesley’s diatribe here; you can read it all and judge for yourself. But as the chapter ends with the police breaking up the demonstration it is evident that Martin has been affected by what he has witnessed:

I won’t share any of Wesley’s diatribe here; you can read it all and judge for yourself. But as the chapter ends with the police breaking up the demonstration it is evident that Martin has been affected by what he has witnessed:

They had stopped the words, but the young man still heard them and would continue to hear them. He saw them rush Wesley off, in a different direction. He would not reach the man; not today. But he would find him. He had to find him.

Because now, for the first time, he knew exactly what he wanted to do with his life.

As I said before, the history and evolution of Freedom’s Hand is a story by itself. I’ll talk about that next week.