This story, first posted in 2012, was a joy to write, and equally to revisit. W.P. Kinsella is, without a doubt, one of my favorite writers.

“Three years ago at dusk on a spring evening, when the sky was a robin’s-egg blue and the wind as soft as a day-old chick, I was sitting on the veranda of my farm home in eastern Iowa when a voice very clearly said to me, ‘If you build it, he will come.’”

These words can be found on a plaque along the Iowa Literary Walk in Iowa City, in honor of author W.P. Kinsella. They are, of course, from Kinsella’s most famous novel, Shoeless Joe, the basis for the screen gem, Field of Dreams.

W.P. Kinsella

I have written enough about Fields of Dreams—if not ad nauseum then at least ad infinitum—my favorite movie of all time, but not nearly enough about the writer whose love of baseball, Iowa, and magical realism made it possible. Time to change that.

William Patrick Kinsella was born in Edmonton, Alberta in 1935. He did not attend college until well into his thirties, first receiving a BA in Creative Writing from the University of Victoria in 1974, and then an MFA from the University of Iowa’s Writers’ Workshop in 1978. He began publishing collections of short stories during and after his time in Iowa, his primary subjects being baseball and First Nations—the indigenous people of Canada.

Kinsella’s link to Iowa ran deep. In an interview published earlier this year on the website The Writing University he said, in his striking prose, “I quickly fell in love with the state—with the rolling fields of corn, the dense humidity, the tall bamboo canes thick as hoe handles. I had never seen the dazzle of fireflies before. I also loved the intimacy of the Iowa River where it snaked, green and lazy, across the University of Iowa campus. There is a spot on campus, along the riverbanks just outside the English-Philosophy Building, where I have decided I want my ashes spread.”

Wanting to show how he felt about Iowa he wrote a short story about a real ballplayer, Shoeless Joe Jackson, who had been banned from baseball—wrongly, most believed—for being involved in a plot to throw the 1919 World Series. His father had often spoken about Jackson. For Kinsella, WHAT IF? kicked in, and the result was Shoeless Joe Jackson Comes to Iowa, the featured story in a collection published in 1980. The expanded novel, Shoeless Joe, was published a couple of years later. About it, the New York Times Book Review said, “Mr. Kinsella is drunk on complementary elixirs, literature and baseball, and the cocktail he mixes of the two is a lyrical, seductive, and altogether winning concoction.”

Wanting to show how he felt about Iowa he wrote a short story about a real ballplayer, Shoeless Joe Jackson, who had been banned from baseball—wrongly, most believed—for being involved in a plot to throw the 1919 World Series. His father had often spoken about Jackson. For Kinsella, WHAT IF? kicked in, and the result was Shoeless Joe Jackson Comes to Iowa, the featured story in a collection published in 1980. The expanded novel, Shoeless Joe, was published a couple of years later. About it, the New York Times Book Review said, “Mr. Kinsella is drunk on complementary elixirs, literature and baseball, and the cocktail he mixes of the two is a lyrical, seductive, and altogether winning concoction.”

Iowa became an acquired taste for me when I met Jacqueline, my wife-to-be, in 1990. Born in Cedar Rapids and a graduate of the University of Iowa, she bleeds Hawkeye black and gold. Using a great line from Field of Dreams, where Ray Kinsella talks about meeting his wife in college, I tell people that when we first met, we realized that we had something in common: she was from Iowa, and I had once heard of Iowa. In any case, W.P. Kinsella’s vivid descriptions of this heartland state have long since come to life for me during our many trips back there.

Though mostly known for his short story collections, Kinsella wrote a few other novels, including another of my favorites, The Iowa Baseball Confederacy. More baseball, more Iowa, more magical realism, and in this one, even Native Americans. What more could I want? The story involves an exhibition game that may or may not have happened in 1908 between a team of all-stars from an amateur league and the barnstorming Chicago Cubs. It’s the 1980s, and Gideon Clark is out to prove that the game indeed took place—perhaps by participating in it himself…

Though mostly known for his short story collections, Kinsella wrote a few other novels, including another of my favorites, The Iowa Baseball Confederacy. More baseball, more Iowa, more magical realism, and in this one, even Native Americans. What more could I want? The story involves an exhibition game that may or may not have happened in 1908 between a team of all-stars from an amateur league and the barnstorming Chicago Cubs. It’s the 1980s, and Gideon Clark is out to prove that the game indeed took place—perhaps by participating in it himself…

In Kinsella’s prose you see and feel the playing surface—the “smell of the grass,” as he calls it. You hear the crack of the bat, the calls of the vendors as they hawk their peanuts and popcorn. The field itself becomes a “character” in the story. You don’t read his stories as much as you participate in them.

Sadly, Kinsella’s writing career was interrupted—almost for all time—in 1997, when he was struck by a car while out walking and suffered a serious head injury. He could no longer concentrate; he lost his senses of taste and smell, and he suffered a personality change. Other than writing occasional book reviews, not much was heard from him. And during this past decade-plus, with all of the changes in the publishing business, he believes he would not be able to break into the marketplace today with his brand of fiction.

Fortunately, the drought ended last year with the publication of a new book, Butterfly Winter, expanded from a couple of short stories that he had written a long time ago. Published by Enfield & Wizenty, a small press in Winnipeg, Butterfly Winter is “the story of Julio and Esteban Pimental, twins whose divine destiny for baseball begins with games of catch in the womb. They mature quickly and by the age of ten they leave their home in the fictional Caribbean country of Courteguay for the American major leagues. They are monitored by the Wizard, a mysterious figure who travels by hot air balloon and controls events behind the scenes. This novel includes a great love blessed by butterflies and a political undercurrent that unites the wealthy north with the baseball-loving and oppressed south.” It is a great read.

Fortunately, the drought ended last year with the publication of a new book, Butterfly Winter, expanded from a couple of short stories that he had written a long time ago. Published by Enfield & Wizenty, a small press in Winnipeg, Butterfly Winter is “the story of Julio and Esteban Pimental, twins whose divine destiny for baseball begins with games of catch in the womb. They mature quickly and by the age of ten they leave their home in the fictional Caribbean country of Courteguay for the American major leagues. They are monitored by the Wizard, a mysterious figure who travels by hot air balloon and controls events behind the scenes. This novel includes a great love blessed by butterflies and a political undercurrent that unites the wealthy north with the baseball-loving and oppressed south.” It is a great read.

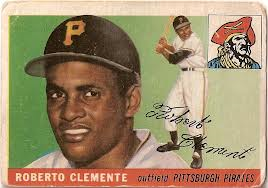

A small taste of Kinsella’s prose: I could share any one of dozens of his short stories, but the one I’ve chosen—among the shortest and one of my favorites—is titled “Searching for January,” which appeared in a collection called The Dixon Cornbelt League and Other Baseball Stories. The true backstory: on New Year’s Eve 1972 the great Pittsburgh Pirates outfielder, Roberto Clemente boarded a plane in his native Puerto Rico on a mercy mission to deliver aid to earthquake-ravaged Nicaragua. The plane crashed at sea and his body was never found.

The story opens in 1987. The unnamed narrator is walking along an unnamed (probably Caribbean) beach: The sand is white as salt but powdery as icing sugar, cool on my bare feet, although if I push my toes down a few inches, yesterday’s heat lurks, waiting to surface with the sun.

He spots a raft at sea, its occupant waving at him. The man in the raft is Clemente, and he says that he is the sole survivor of a crash that occurred—only a few days ago. The narrator, a fan, agrees that he looks like the Clemente of fifteen years ago, age thirty-eight then, but how can this be? His beard is little more than five days’ growth.

The narrator shows him the date on his driver’s license and a 1987 pocket schedule for the Seattle Mariners, who did not exist in 1972. Trying to get his head around all of this, Clemente details what happened before and after the accident. Then he says, “But my wife, my family. Will they all be fifteen years older?” The narrator answers in the affirmative. “My kids grown up?” Indeed.

The narrator shows him the date on his driver’s license and a 1987 pocket schedule for the Seattle Mariners, who did not exist in 1972. Trying to get his head around all of this, Clemente details what happened before and after the accident. Then he says, “But my wife, my family. Will they all be fifteen years older?” The narrator answers in the affirmative. “My kids grown up?” Indeed.

All of his old teammates have retired too. And his Pirates? “Gone to hell in a handbasket,” the narrator says.

So Clemente ponders a while, looks at a path leading to a hotel. Comfort and food. Finally he says, “If I walk up that path, and if the world is as you say—and I think I believe you—I will become a curiosity. The media will swarm over me unlike anything I’ve ever known.”

Ya think? Some things never change. Clemente decides that his choices are all or nothing, the nothing being, “To continue the search.” But how? the narrator wonders.

“I’ve searched for a few days and already found 1987. Time has tricked me some way. Perhaps if I continue searching for January 1973, I’ll find it.”

They discuss other possibilities, and then Clemente says, “I am destined to be found, maybe even on this beach, but fifteen years in your past. I intend to be found. I’ll keep searching for January.”

He pushes the raft back out to sea and climbs in. The narrator: I watch him drift. Trapped. Or am I trapped, here in 1987, while he, through some malfunction of the universe, is borne into timelessness? What if I were to accompany him?

“Wait!” I call. “There’s something…”

But Clemente had already drifted beyond hearing. I watch as he paddles, his back broad and strong. Just as the mist is about to engulf him, as ocean, fog, and sky merge, he waves his oar once, holding it like a baseball bat, thrusting it at the soft, white sky.

A beautiful, touching story—rather sad, when you think of it. How many baseball fans—how many people in general—would have hoped for Clemente to come floating up on a beach—in January 1973? This is the gift of W.P. Kinsella, where baseball and magical realism come together.